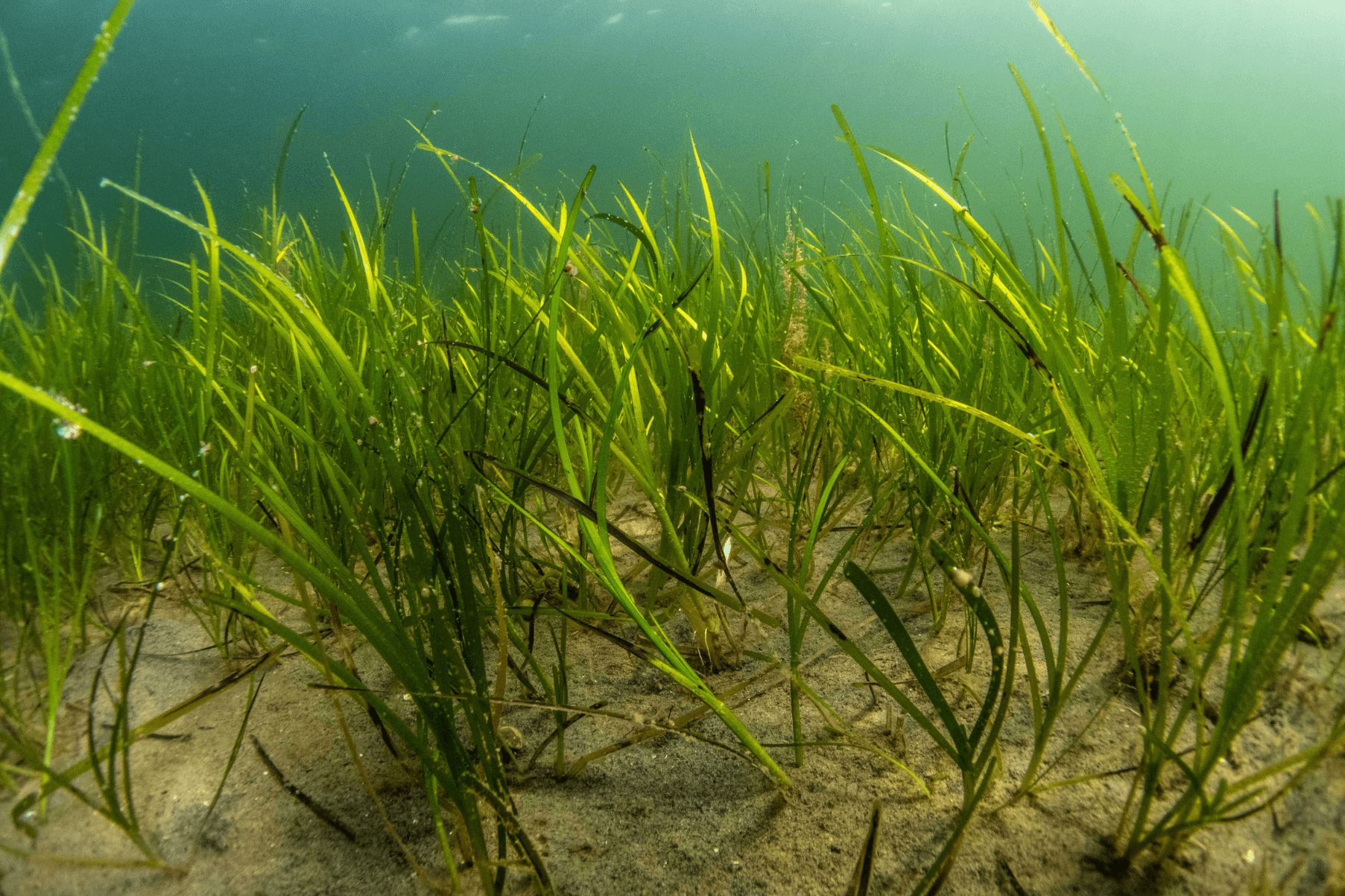

In a new blog series, our Conservation Trainee Abi David explores some of the amazing creatures that call seagrass meadows their home.

Sea snails are a hugely diverse group of marine gastropod found in all over the world. There is such a vast range of different colours, sizes, diets and life strategies within the sea snail community. These are fascinating little creatures that deserve a lot more attention than they receive!

A big issue for sea snails inhabiting shallow coastal areas is desiccation – drying out when the tide goes out. Some species, like periwinkles, will group together in rock crevices and excrete a gluey mucus to hold them in place and retain moisture. A lot of species have an operculum. This structure is attached to their foot and acts as a trapdoor. When the snail retreats into its shell, the operculum will seal shut, preventing moisture from escaping and the snail from drying out.

Snail mating behaviour is both odd and fascinating. There are so many variations in the sea snail world – from self-fertilising hermaphrodites to standard sexual reproduction.

Some species are your standard dioecious set up – within the species there are male individuals and female individuals where gametes from each are needed for reproduction. For example, the common whelk Buccinum undatum has separate males and females. The females will release pheromones to attract males and fertilisation will happen internally, allowing the production of egg capsules. Each capsule contains between 600 and 2000 eggs. Despite being in the same egg capsule, the developing embryo may still have different fathers as the females can mate multiple times and store sperm until the environmental conditions are perfect. Other snail species will gather in groups and release their gametes straight into the water column for fertilisation to take place.

Hermaphroditism is where one individual produces both male and female gametes. Some species such as bubble snails and mud snails are simultaneous hermaphrodites – they can produce both sets of gametes at once, meaning they can self-fertilise. Protandrous sequential hermaphroditism is when the individual started out as male but changes sex to become a female at some point throughout their lives. Species in the genus Crepidula (slipper snails) express this behaviour. The change in sex is thought to be influenced by their social situation – number, sex and size of other individuals in the vicinity.

Some species will carry around their offspring on their shells. Males of the whelk species Solenosteira macrospira will carry the offspring of up to 25 other males. When mating, the female will glue capsules containing hundreds of eggs onto the males shell. As the eggs hatch, some of the first to break free will eat their siblings that are still developing inside the egg. Other species will glue their eggs to solid structures in the environment and leave them to raise themselves.

Eggs can hatch into larvae which will travel with currents to help dispersal and mix populations and then settle down to develop after a few weeks. In other species, tiny, fully formed versions of the adults will hatch.

Why am I telling you about sea snails?

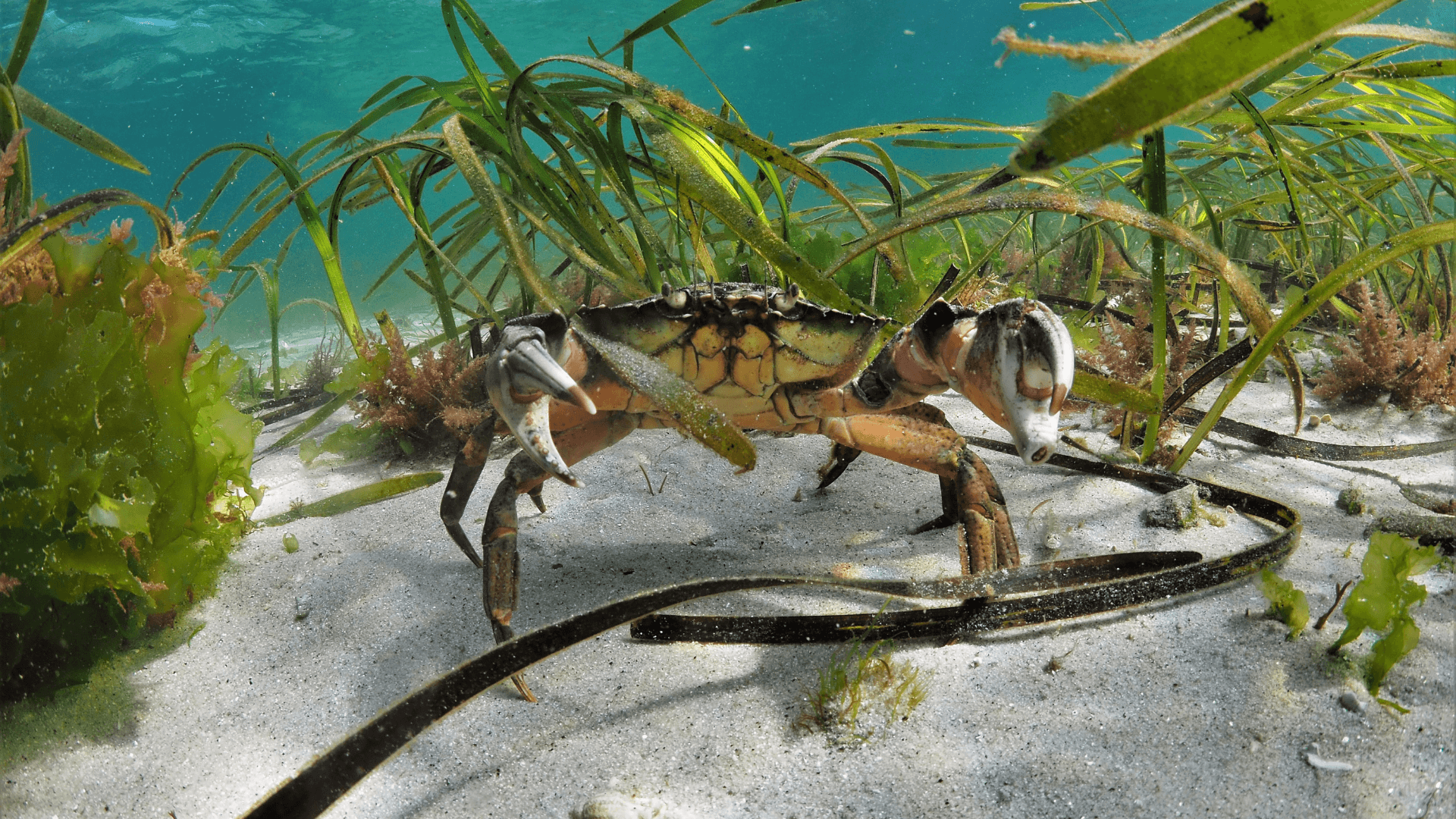

Because they love seagrass! Uk species such as the mud snail Peringia ulvae, banded chink snail Lacuna vincta, the bubble snail Haminoea navicular and perhaps the most recognisable common periwinkle Littorina littorea and netted dog whelk (Tritia reticulata) are all known to use seagrass meadows in at least one stage of their life cycle. Some snails, such as the dog whelk, will lay their eggs on the leaves of seagrass, attaching them with a mucus to hold them firm and preventing coastal currents from dislodging the eggs.

Some species will eat the algae growing on the seagrass leaves. They use sharp, tiny teeth like structures to scrape the algae off the leaves. This is very important for the health of seagrass as too much algal growth will smother the plant, preventing sufficient light for photosynthesis to reach the leaf. There is evidence showing the presence of snails on seagrass increases leaf length and nutrient content (Jiang et al., 2023).

Other benefits of these little critters

Sea snails play a huge role in ecosystems and coastal environments. Their role as an indicator species helps us understand environmental health and can be used to measure levels of pollution and habitat quality. In some cultures, they are harvested for their meat and shells, creating important income streams for coastal communities. Snails form a vital part of many species diets, including birds, crabs and fish. Some species are detritivores – they will eat dead and decaying organic matter on the sea floor. This is a very important role as it prevents nutrient build up which can lead to algae blooms and disease outbreaks.

Sea snails are even being used in scientific research to advance technologies. All snails have tiny teeth-like structures on their radula (a tongue-like mouthpart), however in some species these are super strong. Patella vulgate, a species of limpet, have some of the strongest in the world – the strength of their teeth is comparable to some of the strongest commercial carbon fibres and can withstand the pressures that turn carbon into diamonds (Sea Snail’s Teeth: Are They the Strongest Biomaterials in the World?, 2019). These properties are being studied for use in improving and adapting technology used in building planes, boats and dentistry. Researchers are investigating compounds in the venom some sea snails produce for possible use in medicinal drugs for pain relief and diabetes (Sea snail poison promises new medicines, 2018).

If you want to find out more about these strange little creatures, I’d recommend these articles to start:

References:

Sea snail poison promises new medicines | Research and Innovation. (2018). Projects.research-And-Innovation.ec.europa.eu. https://projects.research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/en/projects/success-stories/all/sea-snail-poison-promises-new-medicines

Eren , R. (2019). Sea Snail’s Teeth: Are They the Strongest Biomaterials in the World? [online] Fountain Magazine. Available at: https://fountainmagazine.com/all-issues/2019/issue-132-nov-dec-2019/sea-snail-s-teeth-are-they-the-strongest-biomaterials-in-the-world.

Jiang, Z., He, J., Fang, Y., Lin, J., Liu, S., Wu, Y. and Huang, X. (2023). Effects of herbivore on seagrass, epiphyte and sediment carbon sequestration in tropical seagrass bed. Marine Environmental Research, 190, pp.106122–106122. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marenvres.2023.106122.