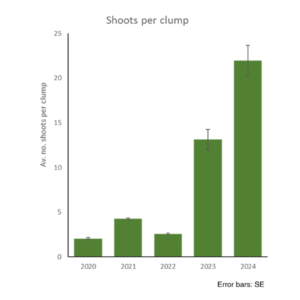

Eelgrass, a type of flowering seagrass found in temperate zones around the world, provides habitat for many species, protects coastlines, improves water quality, sequesters carbon and supports fishing economies. The foundation of a highly productive marine food web, eelgrass’s health is paramount but mysterious. Scientists have long studied how terrestrial invertebrate herbivores such as insects (aphids, beetles) and gastropods (snails, slugs) frequently act as vectors, transmitting plant diseases through their feeding activities and often creating wounds on plants’ surfaces that make it easier for pathogens to enter. But how this works, and how pernicious the problem is, has been harder to study underwater in the ocean. In two new papers, Cornell plant-herbivore experts and researchers from the Cornell Institute for Computational Sustainability joined forces to show the significant impacts of herbivores like sea snails on the spread of seagrass wasting disease. Grazing by small herbivores was associated with a 29% increase in the prevalence of disease, which contributes to huge losses in meadow areas from San Diego to Alaska. The two papers are “Invertebrate Herbivores Influence Seagrass Wasting Disease Dynamics“ and “Seagrass Wasting Disease Prevalence and Lesion Area Increase with Invertebrate Grazing Across the Northeastern Pacific,” the former published in the December 2024 issue of Ecology, and the latter in the January 2025 issue. The research brings together the work of Drew Harvell, professor emerita of marine ecology in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology; Olivia Graham, a marine disease ecologist and postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology; Lillian Aoki, an eelgrass ecologist and former postdoctoral researchers in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology; Carla Gomes, the Ronald C. and Antonia V. Nielsen Professor of Computing and Information Science, director of the Institute for Computational Sustainability, and a Schmidt AI2050 Senior fellow; and Brendan Rappazzo, doctoral student in computer science. “The cool thing about these two papers coming out at the same time is that they are two ends of the same project, from controlled lab experiments to continental scale field surveys” Harvell said. “This is pioneering work in an understudied system, the first study to show the role of these herbivores in facilitating disease at a huge latitudinal scale.” Their work shows that isopods and snails create open wounds on eelgrass when they graze; lab experiments verify increased disease in the wounded plants. The researchers also showed that sea creatures can be picky eaters: Crustaceans called amphipods selectively consumed diseased eelgrass, while the isopods and snails prefer to feed on pristine leaves, meaning different herbivores have contrasting impacts on seagrass health. Gomes and Rappazzo have accelerated the effort to identify and quantify the problem via the Eelgrass Lesion Image Segmentation Application (EeLISA, pronounced eel-EYE-zah), an AI system they have developed that, when properly trained, can quickly analyze thousands of images of seagrass leaves and distinguish diseased from healthy tissue, thus allowing continental scale studies. (a) Evidence of snail grazing (left) that damages leaf surfaces in contrast to crustacean grazing (right) that consumes the full thickness of the leaf tissue (photo credit Lillian R. Aoki). (b) Across all meadows and years, leaves with grazing scars were more likely to be diseased; labels show counts of leaves in each category and box widths are proportional to the count (total n = 1351). Credit: Ecology (2025). DOI: 10.1002/ecy.4532 Researchers collected thousands of eelgrass leaves at 36 sites along the Pacific Coast from Southern California to Alaska, uploading high resolution images of each plant. Gomes and Rappazzo used algorithms and machine learning to train a computer using state-of-the-art image segmentation to recognize necrotic dark spots on eelgrass blades and correctly identify them, separating disease-caused lesions from other kinds of leaf damage. “We came up with a positive feedback loop,” Rappazzo said. “Researchers Olivia Graham and Morgan Eisenlord would correct EeLISA, which would update immediately. When a new set of samples would come in, the AI would do better immediately. The accuracy is more consistent than humans, which allows for scalability—to have humans analyzing the images by hand would take 20 minutes per image. EeLISA can do it in a second. The whole continental-scale study took 30 minutes to run.” Gomes describes Eelisa as a novel AI approach to solve impactful real-world problems. “The collaboration has removed the historic bottleneck of interpreting data,” Gomes said. “We continue to enhance Eelisa with the capabilities of multimodal language models, enabling it to explain its scientific reasoning—why it determines the presence or absence of disease. It can also engage in conversation with researchers, making the process more interactive and insightful.” “Working with Carla and Brendan has allowed us to do so much more work,” Graham said. “Eelgrass is globally distributed and it’s not an exaggeration to say these seagrass meadows have superpowers. They are our rainforest of the sea. As incredibly valuable habitat for marine fish and vertebrates, they support vital fisheries.” Recently, international researchers have contacted Graham with requests for access to EeLISA, she said. There are a number of global stressors for seagrass meadows, especially as ocean temperatures rise, but Graham, who leads the deeper-water SCUBA surveys and lab experiments, came at the question as a disease ecologist, asking first if these herbivores were directly transmitting pathogens. The answer was no, it was indirect transmission, the bite marks providing an entry point for infection. Better knowledge of both the mechanisms—both how herbivory can influence disease as well as the ecological impacts—is needed, said Lillian Aoki ’12, lead on the second paper and an ecosystem ecologist and coastal scientist at the University of Oregon. “We need to know when and where herbivory might be important to disease dynamics and ecosystem stability,” said Aoki, also a former postdoc in Harvell’s Cornell lab. “This information will help us to better predict changes, such as disease outbreaks, and to manage coastal habitats.” More information: This article is republished from PHYS.ORG and provided by Cornell University. Olivia J. Graham et al, Invertebrate herbivores influence seagrass wasting disease dynamics, Ecology (2024). DOI: 10.1002/ecy.4493 Lillian R. Aoki et al, Seagrass wasting disease