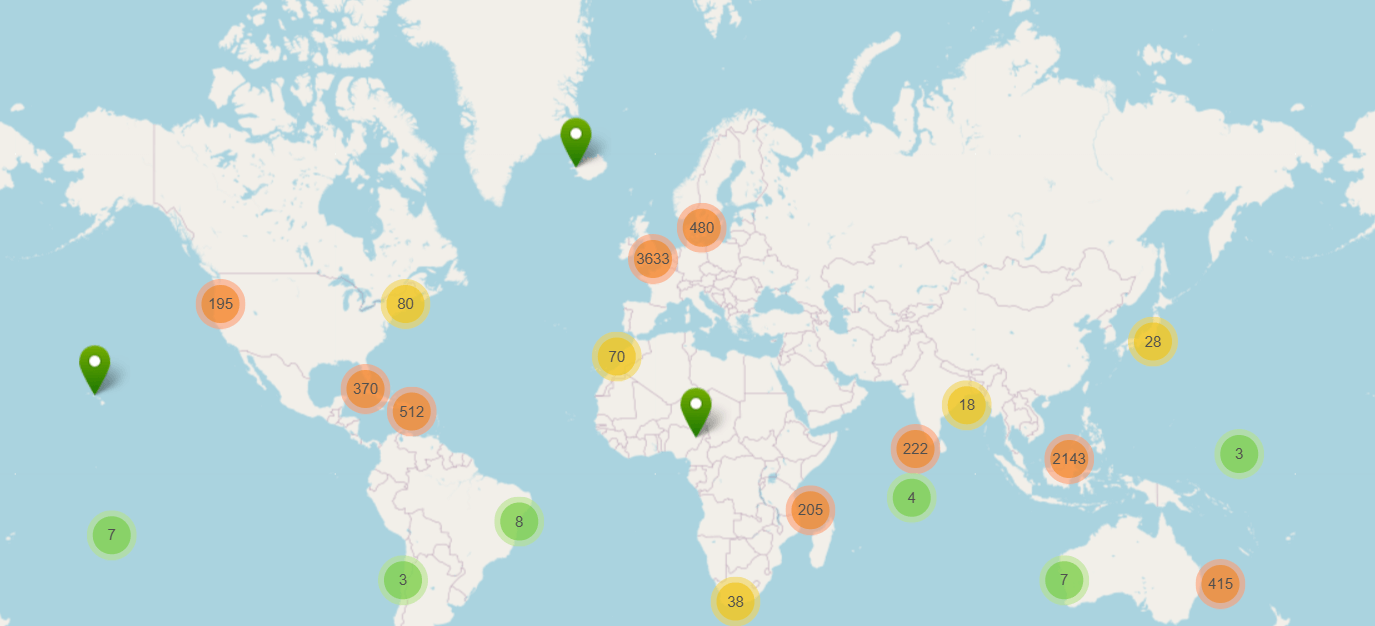

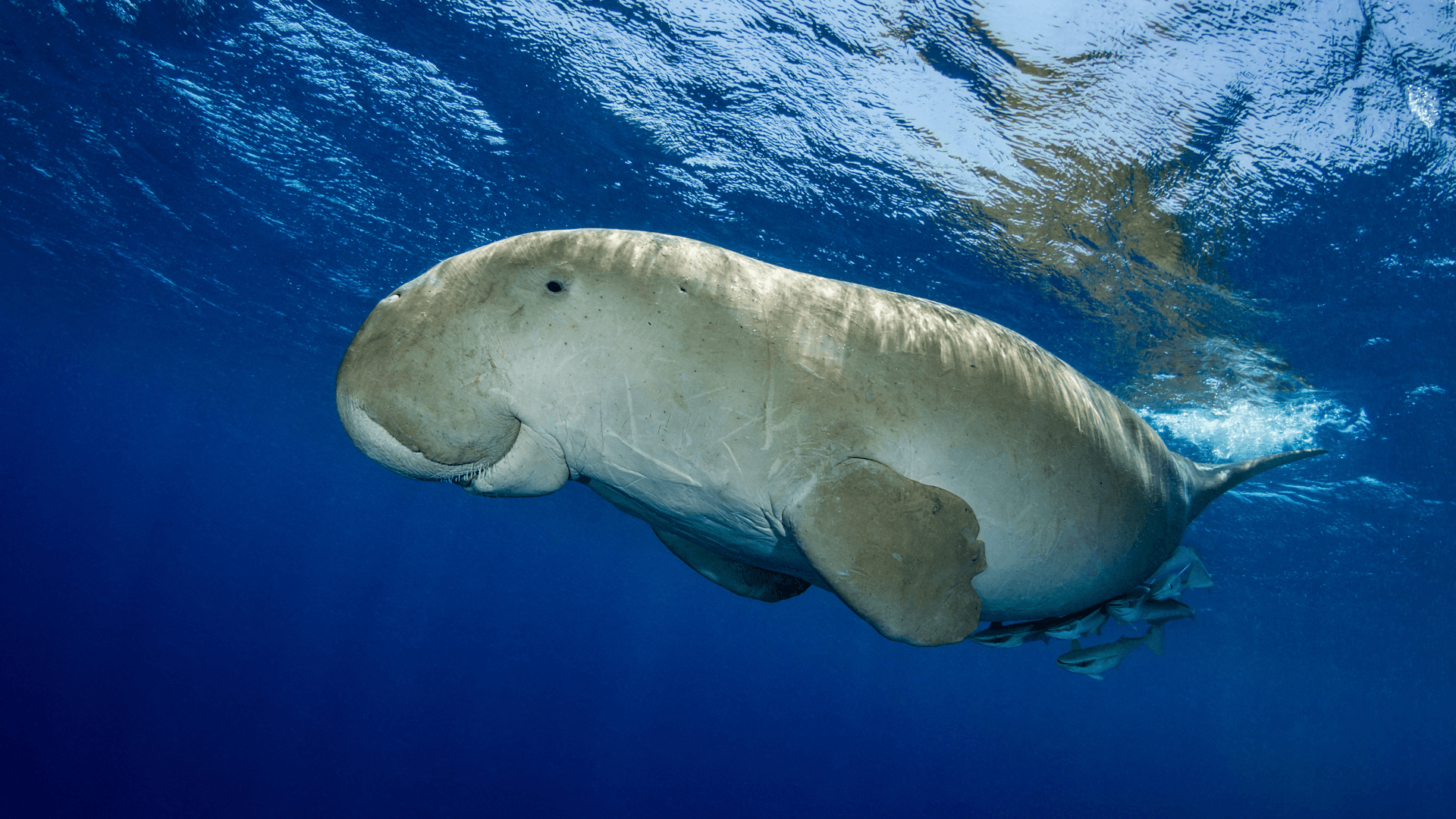

This article was originally published on Dialogue Earth under the Creative Commons BY NC ND licence. The author is Siripannee Supratya. Siripannee Supratya (Noina) is a Thai journalist focusing on the environment, science, laws and socio-political happenings. In addition to her journalism work, she is a creative communicator and a professional diver. She is on Bluesky and X. When Piyarat Khumraksa started combing through five years of Thai government data on dugong deaths, she did not anticipate uncovering a crisis of national significance. The Department of Marine and Coastal Resources (DMCR) had recorded far more deaths in 2023 and 2024 than previous years, but the reason was not clear. Khumraksa is a marine veterinarian who works along southern Thailand’s coastal provinces of Krabi, Trang and Satun. She is based at the Marine and Coastal Resources Research Centre, overlooking the lower Andaman Sea. Here, once-thriving seagrass meadows have been disappearing, along with the dugongs that rely on them for sustenance. “We first noticed problems with the seagrass five years ago, but it became critical in 2023 and 2024,” Khumraksa says. “The dugongs that were living in this area have now migrated to find seagrass along the west coast in Phuket, Phang Nga and Ranong provinces. This is the first time we have witnessed such a thing happening.” When dugongs are washed ashore in Thailand, they are rarely alive. A deceased animal that washed up in Krabi province on 30 December brought the total death count to 45 last year. In 2023, there were 40 deaths. In October 2024, the minister for natural resources and the environment, Chalermchai Srion, stated that dugong mortality in Thailand usually averages 13 per year. Stranding hotspots are concentrated in Trang province, especially around Mook and Libong islands. Khumraksa says this is where previously vast seagrass beds have vanished. Dialogue Earth spoke to Milica Stankovic, who works in the lab at the Seaweed and Seagrass Research Unit at southern Thailand’s Prince of Songkla University. She shares the example of Krabi’s Ao Nammao Bay, where seagrass coverage has plummeted from a healthy 60%, to 1% in 2024. A leading theory behind the seagrass die-off is changes in global climate patterns that trigger cascading effects. One of those effects is unusually low tides around Thailand, which fatally expose swathes of seagrass. Various efforts are now being made to support Thailand’s dugongs, including seagrass restoration. But there are fears the population will not be able to recover to its former size. Plummeting numbers According to a DMCR survey, Thailand had 273 dugongs in its surrounding waters in 2022, mostly living along the west coast in the Andaman Sea. Based on recorded deaths alone, Thailand may have since lost around one-third of that population. The true toll may be even higher, as many carcasses likely go undiscovered. Dugongs are categorised as vulnerable on The International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species. That is one stage before endangered. The only purely marine grazing mammal alive today, they feed almost exclusively on seagrass. This was once abundant in the warm, shallow waters of the Andaman Sea off south-west Thailand. Historically, dugongs were hunted for their tusks, meat and even their tears, which were used for their supposed aphrodisiac properties. They have been protected under Thai law since 1961. Today, hunting poses less of a threat, as the spiritual significance of the dugong has evolved to protective respect. The animal has also become valued for its appeal to ecotourists. Despite this legal protection, the trend of losses highlighted by Khumraksa raises worrying questions. Many of the dugongs that washed out of the Andaman Sea between January 2019 and November 2024 were emaciated. Only 12% of dugong deaths could be attributed to direct anthropogenic factors, such as fishing gear entanglement or boat collisions. While some tusk poaching was observed, Khumraksa says this appeared to be opportunistic and occurred after death. According to autopsies, plastic ingestion was also minimal, ruling out this pollution as the primary cause of death. In 40% of dugong deaths, the exact cause could not be determined due to advanced decomposition. Khumraksa says she has begun seeking out help from universities and researchers, so that she might investigate what constitutes “natural causes” among these deaths. She wants to establish whether starvation, disease, or a combination of factors could be responsible for the recent spike. So far, her own findings already point to a clear trend: as seagrass meadows decline, dugong deaths increase. Low tides and no green grass While many researchers are linking seagrass decline to the rise in dugong deaths, the authorities remain cautious. The DMCR’s director-general, Pinsak Suraswadi, cites other factors – such as disease, grazing pressure from other species and habitat damage from coastal developments – that could also be contributing to the crisis. Nevertheless, the widespread loss of seagrass remains a major concern. While seagrass naturally experiences seasonal variations, experts stress the current level of degradation is unprecedented. Suraswadi tells Dialogue Earth that researchers are working to establish what is causing the seagrass die-off. A key theory points to the prolonged exposure of intertidal seagrass to air, which is occurring during unusually low tides. “Data from 2023 shows water levels at low tide are lowered by 20-30cm – the seagrass gets exposed for a bit longer,” explains Suraswadi. “Seagrasses in deeper zones survive, but then they have grazing pressure from other surviving marine animals that also feed on seagrass.” Suraswadi attributes this retreat to natural, recurring variations in oceanic and atmospheric conditions called climate oscillations. The famous El Niño/La Niña system is one of these, but there are several others. It is not yet clear what exact oscillation may have caused the recent low tides, but, combined with higher-than-normal air temperatures, some experts think this change could have driven Thailand’s seagrass into trouble. “These past few years, low-tide marks have been dropping lower, exposing seagrass to extreme temperatures for longer periods,” says Suraswadi. “This has made us realise we need more expertise in physical oceanography [to fully understand the impact on marine ecosystems].” The Seaweed and Seagrass Research