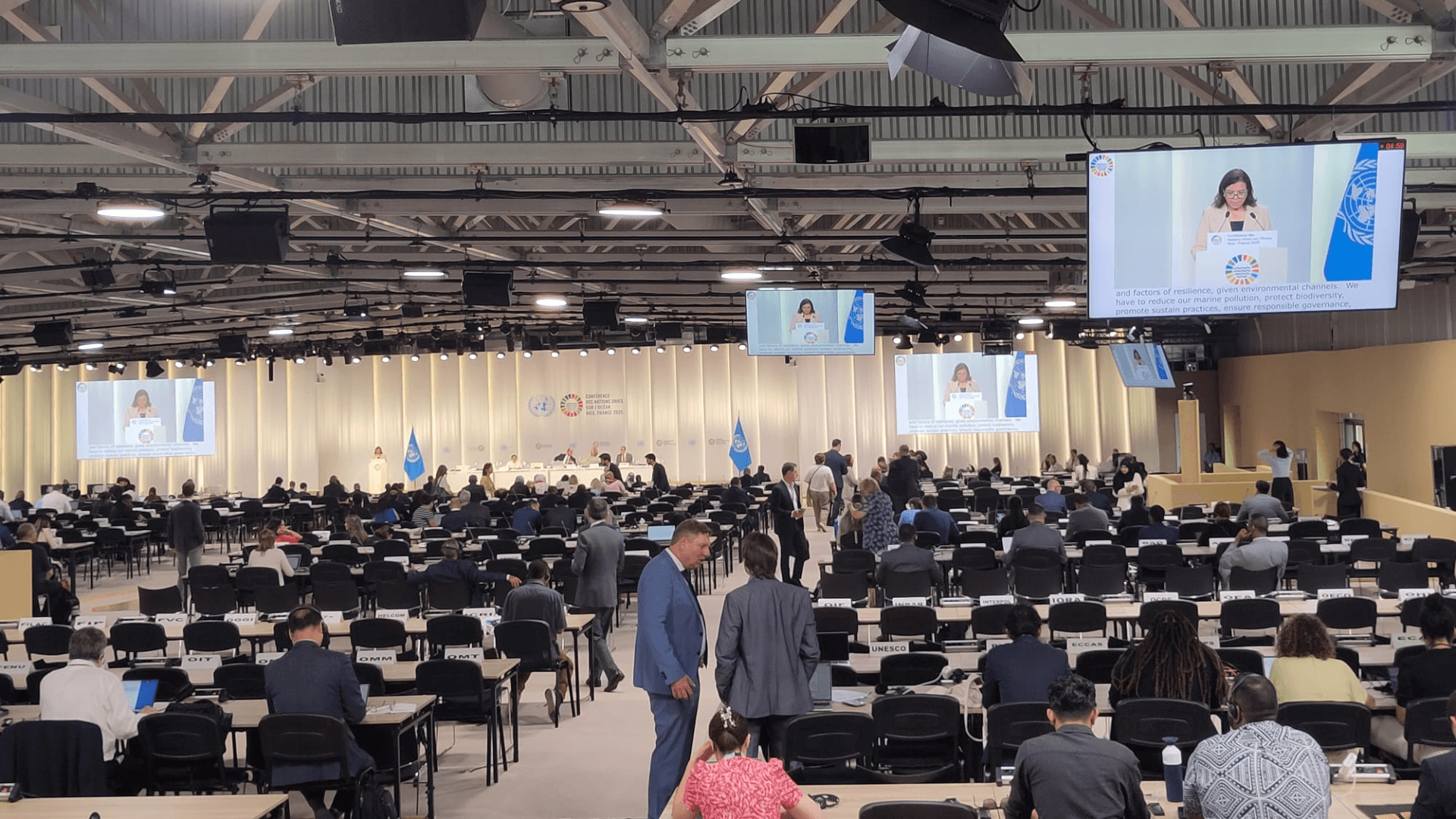

In this article, Project Seagrass CEO Dr Leanne Cullen-Unsworth reflects on the United Nations Ocean Conference: The 2025 United Nations Ocean Conference, co-organized by Costa Rica and France was held in the coastal city of Nice, France from 9 to 13 June. Over 15,000 people participated, including 2,000 scientists and more than 60 world leaders. Discussions aimed to shine a light on the challenges of unlocking sustainable ocean investment and how to reinforce the role of marine science in policymaking. Our Project Seagrass team was delighted to be able to attend and contribute to the Conference receiving special accreditation to join the full programme by the UN. The Conference was insightful, inspiring, hopeful, overwhelming, challenging, in short it evoked an epic rollercoaster of emotions both negative and positive respectively around the declining health of our oceans and the demonstrated passion to drive change shown by individuals from across the globe. There was much conversation about David Attenborough’s ‘Ocean’, with divided opinion on the contents and emphasis of the film. For me, this was Sir David doing what he does best and providing an engaging and heartfelt narrative to grip a generalist audience of millions and share the beauty and importance of our ocean whilst highlighting a very real and current threat. Regardless of opinion, the impact of ‘Ocean’ was clear as a persistent thread through the narrative of the conference, and subsequent commitments from governments across the globe to strengthen protection of designated marine areas. This includes the UK Government proposing bottom trawling bans in all English offshore marine protected areas. It’s a start, but we need continued public pressure to ensure a move from proposal to action. We also need much bigger commitments to save our ocean which in turn, if healthy, will respond to the nature and climate crises we are facing. It was encouraging to observe in the Blue Zone some high-level dialogue drawing the connections between land and sea, with even land-locked countries demonstrating interest in ocean health and their impact on it. It’s critical that we target preserving and increasing biodiversity across environmental boundaries for sustainable futures. It’s also clear that we’ve actually moved beyond a need for sustainability. To sustain is to maintain in the same state, when what we so clearly need is environmental recovery at scale and through a connected approach. We will not achieve any environmental or human wellbeing targets taken in isolation. It was repeatedly acknowledged that the ocean is our lifeline, and not just for the 40% of humanity living along coastlines or three billion people reliant on seafood across the globe, but for everyone. Our ocean and the biodiversity it contains sustains life on our planet as we know it. Every part of the global ocean in important, and every part is threatened. Coastal waters, containing 70% of marine biodiversity, are particularly vulnerable at the interface of land and sea with both land-based and ocean-based threats having an impact. Lots of emotive statements were made, all the right words but the associated specific actions needed to drive change and achieve any targets seem elusive. There also seemed to be an imbalance in terms of habitat representation. Seagrass was one coastal habitat receiving limited attention at the United Nations Ocean Conference. Which highlights that there is still much to do to gain acknowledgement that this is a critical habitat alongside, for example, better understood coral reefs, mangroves, and saltmarshes. Seagrass is a habitat that underpins marine biodiversity and delivers a wide range of ecosystem services vital to planetary health, climate resilience, and human wellbeing. Seagrass does this to varying degrees across its near global range. Seagrass systems contribute to targets within all the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Yet, they remain underrepresented in global scale conservation and climate initiatives, and on the formal programme at such a significant conference. UNOC3 was held at the midpoint of the UN Ocean Decade. A decade dedicated to delivering the science we need for the ocean we want. But five years into the decade, our oceans remain far from recovery. We are not on target to meet Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 14 (life below water) which means we will also be unable to meet other dependent SDGs. Knowledge is improving and the science is clear, but we need to be better at sharing and building on each other’s advances. We also need clearer pathways to influence decision making. In fact, the conference highlighted multiple needs for any chance of achieving ocean recovery at scale. This list is long, but here are just a few examples: We need explicit processes for different sectors to be able to contribute the vast amounts of data that is currently sat on inaccessible hard drives or within unsearchable grey literature. There were repetitive calls for both new and existing data to be shared, this sharing of data and knowledge would serve to turbocharge rather than duplicate efforts on the road to planetary recovery. This goes hand in hand with a need for improved funding for evidence based environmental recovery practices. For me this shouldn’t be an emphasis on initiatives towards financial gain for investors but rather an investment in the resource that sustains and fulfils us all. Too often that connection feels lost, which is disheartening and concerning. Governments need to analyse and respond to the needs of communities. How do they do this? They need data! And sectors within Governments need to work together and pull in the same direction with coordinated approaches. We need to communicate effectively beyond disciplinary, national, and sector boundaries. Finding common language is challenging. Another recurring theme. Critically, we need people to reconnect with nature, and possibly more than that, recognise that we are nature – we need trees, fish, saltmarsh, seagrass and all the wellbeing benefits that they provide – people are disconnected and that’s a big problem. This raises questions of justice and equality, social justice is needed to improve our shared environment. The conference concluded with the adoption of a political