A guest blogger? But why should I bother reading what he has to say? Well here’s a bit about me….

Originally hailing from Melton Mowbray, a small town in the middle of England known solely for producing pork pies and stilton cheese, my initial foray into marine science began with any other child’s obsession with the beach. My parents often remind me that after hours of poking around in rockpools and catching crabs I would throw tantrums when it was time to leave the coast and return to my landlocked home. As I became older and words like career and jobs became ever more prevalent in my life, I began searching for the holy grail of adult life, a job which I genuinely enjoyed.

This search led me to undertake a Bachelor’s degree in Coastal Marine Biology in the now non-existent Scarborough Campus of the University of Hull; I should clarify that my class was the last year to graduate from that tiny seaside town before the satellite campus shut down. It was during my time as an undergraduate researching in the Aegean Sea that I first encountered seagrass ecosystems and immediately fell in love. Seagrasses are the only true marine angiosperm (flowing plants) and have been described by Professor Carlos Duarte (a famous seagrass scientist) as ugly duckling ecosystems. After returning from that career changing trip all my subsequent assessments were targeted towards seagrasses as I endeavoured to learn all I could about their function, ecology and reproduction.

A room with a view… daily scenery when completing Aegean seagrass surveys.

This obsession permeated through to my Master’s degree at the University of York in Marine Environmental Management where my supervisor shared a passion for these underappreciated ecosystems; it seemed fate had brought two seagrass nerds together at last. As I continued through the MSc with a specific focus on seagrasses when possible there came a time where I had to find an external placement partner to complete my second thesis with. Being still constrained firmly to the student financial situation I did not have the prospect of travelling to far flung places as some of my peers. However, this hardly mattered as my first choice was to work with the only active group of seagrass researchers in the UK, Project Seagrass! After finalising the logistics of the project and “upping sticks” to Cardiff in mid-July I now right this blog post sat at a desk in Project Seagrass HQ nestled in a surprisingly sunny Cardiff.

But that’s enough about me, let’s talk seagrass citizen science!

The project I am completing investigates the motivations, benefits, barriers and changes in knowledge associated with taking part in seagrass citizen science projects, specifically SeagrassSpotter and Seagrass-Watch (follow the links if you want to learn more about these projects). More broadly the project sets out to discover who is taking part, why they take part and when they take part. The project itself is being co-managed by myself and Isadora Sinha of Cardiff University who is heading up the demographics (the who) associated with the project.

Throughout the project we utilised an online questionnaire which has been disseminated to current users of SeagrassSpotter, Seagrass Watch, and various seagrass-based email and social media groups (yes seagrass Facebook groups exist, if you’re interested you should join one). Given that citizen science, the participation of non-scientists in scientific research, has been labelled as a source of large data sets across varied space and time, seagrass citizen science has the potential to alleviate some of the primary threats these ecosystems face.

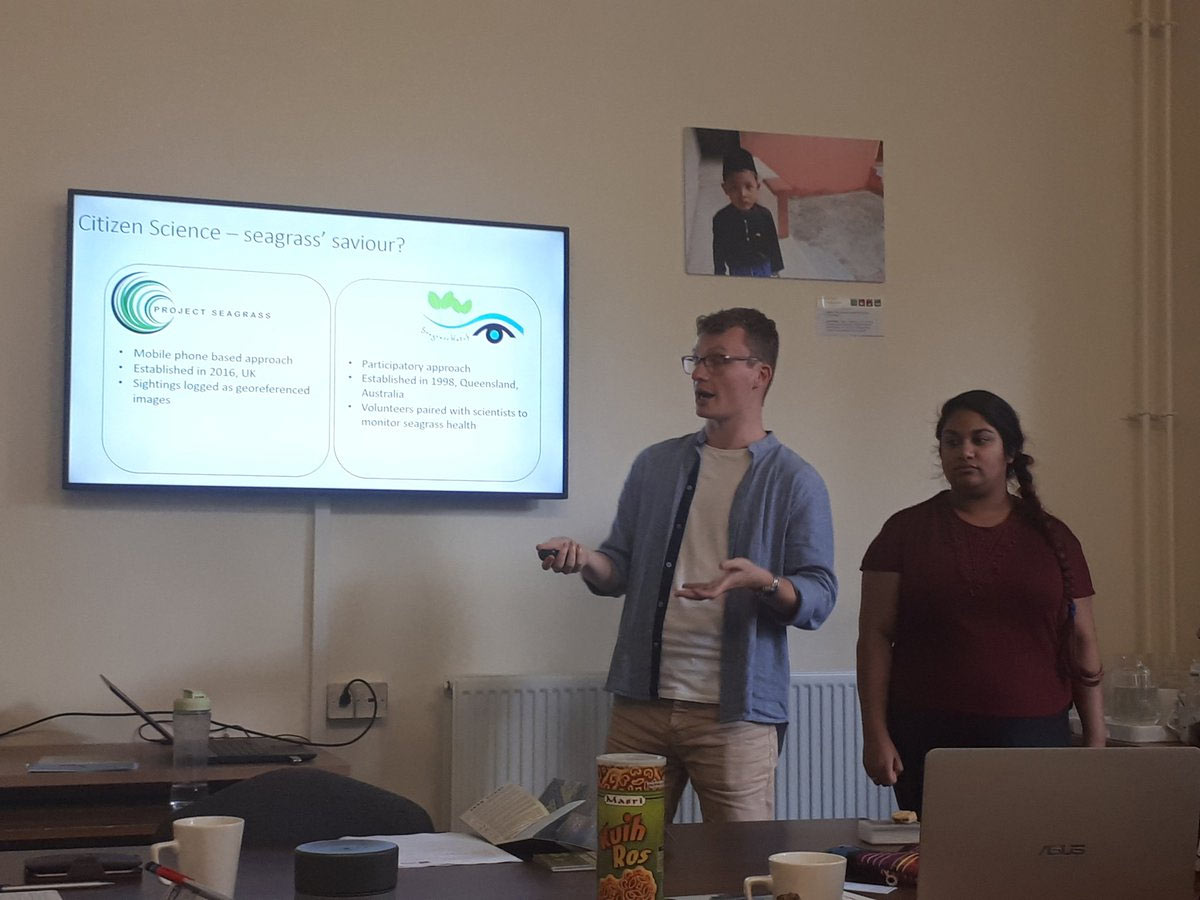

Talking all things seagrass citizen science at a workshop organised by Cardiff University.

Talking all things seagrass citizen science at a workshop organised by Cardiff University.

Seagrasses are thought to be declining at around 7% a year, with declines primarily due to changes in water quality and increases in suspended sediments which reduce the ability of the plant to photosynthesise by blocking available sunlight. Additionally, researchers have little idea of local spatial coverages of seagrasses due in no short part to a chronic lack of public awareness of their existence; a concept which doesn’t apply to more charismatic ecosystems such as coral reefs.

This decline represents not only the loss of a beautiful marine habitat (see the photo below if you don’t believe me) but also the services these ecosystems provide. Seagrasses are present on the coastal fringes of almost all continents worldwide where their presence promotes high primary and fisheries productivity, in turn supporting food security worldwide. You know the cod that forms an integral part of your chippy tea? Well it probably spent a good part of its juvenile years living in and around seagrass meadows. Seagrasses also add 3D structure to muddy bottoms, enhancing sediment capture which stabilises coastlines against erosion and acts to trap carbon dioxide helping to combat climate change.

It is therefore hoped that by better understanding why people take part in seagrass citizen science we can reduce barriers to participation and increase public awareness and conservation of these crucial ecosystems. The project also represents the first time these topics have been studied in a seagrass specific context so will provide much needed insight into the finer state of seagrass citizen science. For a global review of seagrass citizen science see this article led by Project Seagrass Director Benjamin Jones (sorry, it’s not open access).

At the time of writing the survey has been sent to over 1000 people and has been completed around 60 times. This may not seem like a worthwhile return, but such a small number of responses is common among online surveys.

Results from the survey are being collated currently and will be prepared ready for my MSc thesis submission in early September. So, watch this space for seagrass updates!

Together we can promote conservation and raise awareness of seagrasses to help this ugly duckling become beautiful swan.