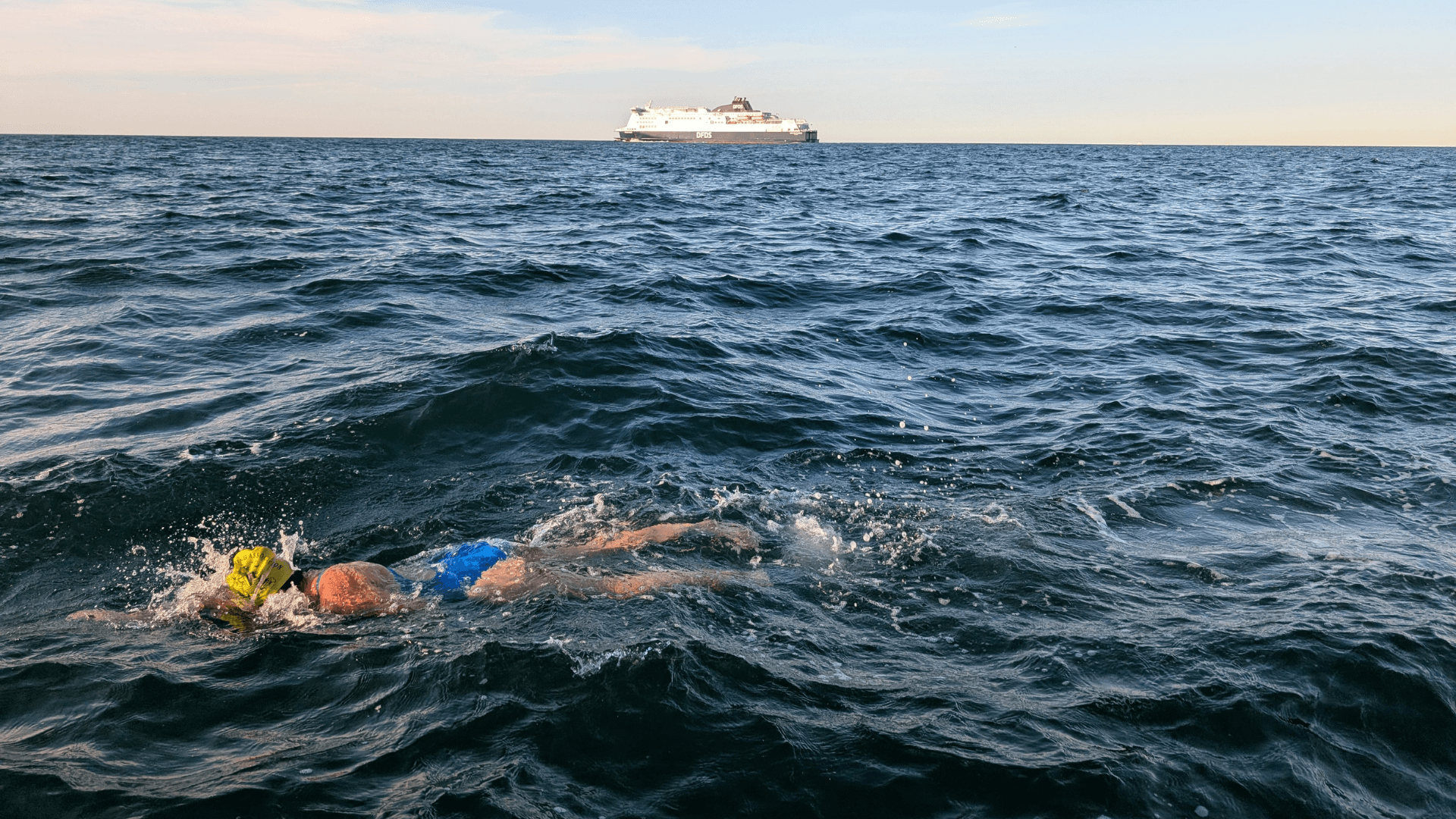

Successful swim to support seagrass

In a guest blog post, Laura Suggitt shares her experiences of swimming the Channel to raise vital funds for environment funds including Project Seagrass: Earlier this month, I swam across the English Channel to France with my team, The Matriarsea. We completed the crossing in 12 hours and 49 minutes; swimming 35 miles in total as a result of the tough tides. It has long been a dream for me to cross the Channel and reaching France in the sparkling sunshine with the strong women in my team around me was magical. I was swimming in memory of my brother Henry and we raised over £6,000 for three charities: Project Seagrass, Planet Patrol, and Surfers Against Sewage. I am so proud of the team, and it is such a privilege to be their captain. Yet, behind the sparkling sunshine and smiles, its easy to forget that our journey to get there was far from smooth… We were originally scheduled to swim in June – but the winds were too high throughout our tide window and it wasn’t safe. We responded by designing our own challenge and swimming double the distance in Dover Harbour; through sewage, high wind and freezing water. It was brilliant and I am still particularly proud of how we turned our initial disappointment into something amazing. But there was a part of me that didn’t want to give up on the original dream. I knew, if the weather was right, we could do something really special. So, when a cancellation came up for August, I took the chance. But the weather still wasn’t playing ball. Then, with 24 hours notice, our pilot rang me up and gave me a choice, to try outside of the main tide window and do our best to make the crossing. He warned me the tides were aggressive, and there would be huge swell, but if we swum hard we might be able to make it. It would be our very last chance. We decided to take the risk. So against all the odds, we left Dover Harbour at 2am on Monday morning. The first 5 hours were gruelling. Seriously nauseating conditions on the boat, and 4ft swell in the water, swimming in the middle of the Channel in the pitch black. I’ll be honest, we were all terrified, but we dug deep. Then came the really aggressive switch of tide at sunrise. I had to swim the hardest I ever have to salvage our crossing or we’d be pushed into a freight lane. That’s not to mention jellyfish the size of dinner plates, the huge swell, no sleep, the stench of diesel, sewage slicks, and buckets of seawater swallowed. And it took sweat and tears to even start. A year of planning, rallying after opportunities didn’t materialise, early morning swims around work, sessions that pushed us to our edge, adapting to freezing water, and the mental gymnastics (and maybe insanity) it takes to jump into the Channel at night and swim your guts out. There were many reasons we shouldn’t have made it, but we did. We were extremely lucky to have amazing supporters, and most of all each other, to lift us when things got tough. This was one hell of a lesson in what it takes to never give up and I hope something in our story resonates. I am so proud of these women, and I’m so proud to be a woman. We really can do anything. Project Seagrass is most grateful to The Matriarsea team for raising funds to support our work to save the world’s seagrass. Project Seagrass is extremely grateful to The Suggitt Family for their generous support for the Henry Suggitt Laboratory (named after Laura’s brother). Find out more about the lab here.

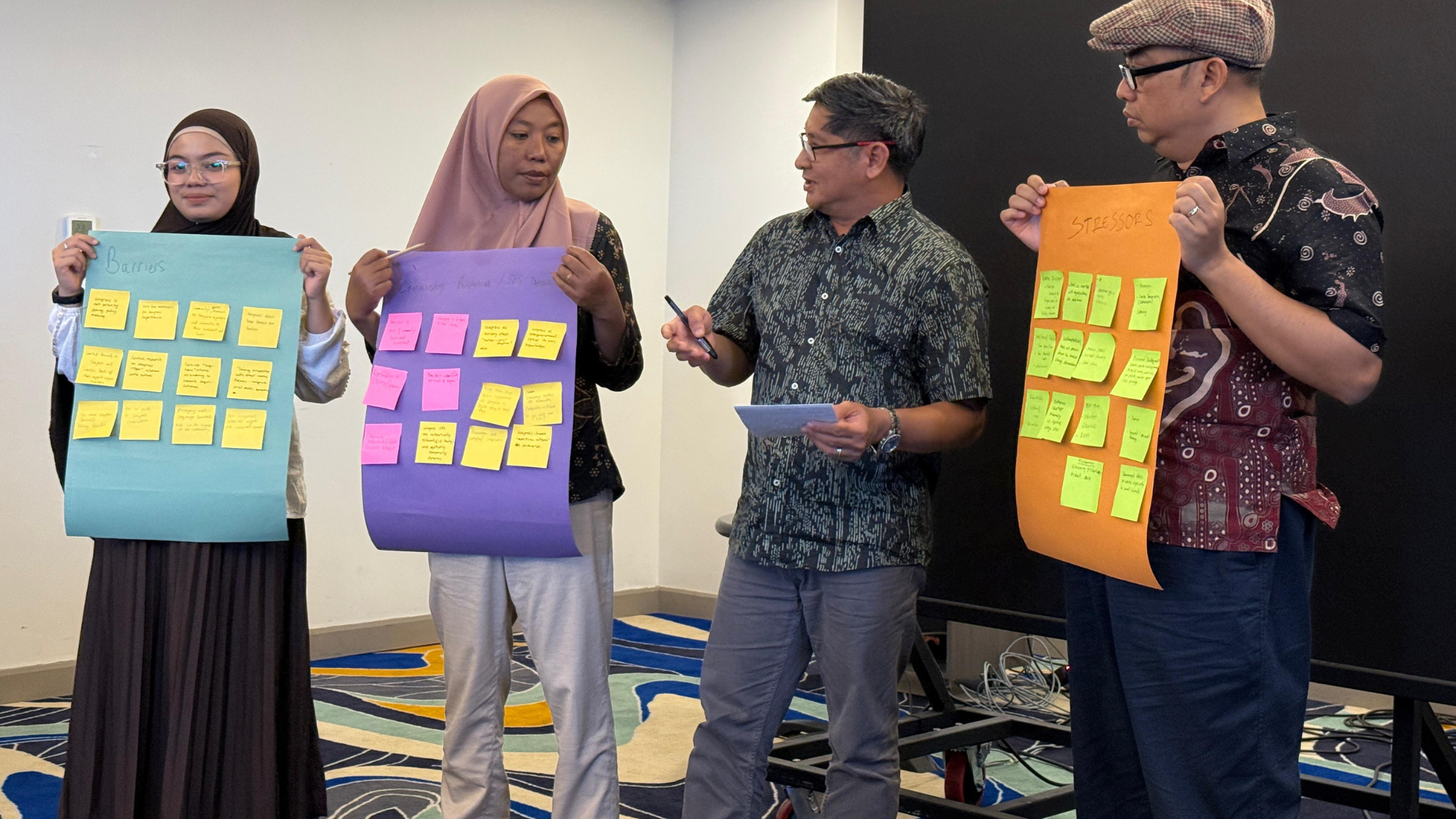

Reflections from the Seagrass Knowledge for Action in Southeast Asia Workshop

This summer, teams came together in Makassar, Indonesia, for the Seagrass Knowledge for Action in Southeast Asia workshop to explore pathways forward for strengthening knowledge, building research capacity, and development to further safeguard local seagrass social-ecological systems. Co-hosted by Universitas Hasanuddin (UNHAS) and Project Seagrass, the workshop involved teams from across Indonesia and the Philippines including Forkani, Yapeka, and C3 (Philippines) who joined forces to discuss highlights, setbacks and future dreams for seagrass conservation, protection and restoration in their local contexts and more broadly within the region. The workshop provided an opportunity to discuss our plans for future collaborative work in Southeast Asia, building upon work undertaken through the Seagrass Ecosystem Services project. Partners discussed pervasive threats to seagrass within each of their local study regions and explored the numerous commonalities between their organisation’s locations. In addition to threats, the limitations that prevent partners from addressing these threats and undertaking social-ecological research were identified. A diverse and numerous array of research and capacity building barriers were discussed which were associated with governance, social, ecological, socio-cultural, cultural, spiritual, logistical, and funding limitations. Though nuanced, and taking different forms for each organisation, the identification of these barriers provides essential context for helping to develop research and build local capacity in partner organisations. Each partner discussed their research priorities which concerned many dimensions of seagrass social-ecological systems and the just protection and conservation of seagrass meadows for food security, poverty alleviation, cultural importance, and local livelihood support. Through these conversations, partners explored the spaces within these research priorities that require conservation actions, what these actions may well be, and what support may be required to bring these priorities to reality. Following these in-depth discussions partners also worked on shaping a paper focusing on persistent threats and urgent calls to action to reduce these threats. From 2026, Project Seagrass’ international strategy will also include grant giving, which has been co-conceptualised and developed with local NGO’s, and has been evidenced by others.

The Brent Goose: Creatures that call seagrass home

In a new blog series, our Conservation Trainee Abi David explores some of the amazing creatures that call seagrass meadows their home. The Brent Goose Branta bernicla is of a similar size to a Mallard duck, making it one of the smallest goose species in the world. They are a highly social species and form strong bonds within the groups they live in. If you spot a group of Brent Geese, look out for the ‘compass’ goose – this is the leader of the group and will lead the way between foraging areas. Depending on the species of Brent Goose, individuals may have a dark or light belly, along with a dark head and body, with adults having a small white patch on their necks. They can be seen throughout the UK during the autumn/ winter months in marine, intertidal or wetland areas. Dark bellied Brent Geese. Photo Credit Emma Butterworth Migration Just like many other bird species, Brent Geese carry out an annual migration. They spend summer months breeding and raising chicks in the Arctic and migrate to Western Europe for more temperate winters. Generally, the individuals we get overwintering here in the UK are from Siberia. Due to these long migration routes and small body size, Brent Geese have a high food demand meaning they heavily rely on stopovers to refuel. Their most popular stopover sites tend to be Zostera marina meadows. Large numbers of Brent Geese have been spotted for several weeks each year in Izembek Lagoon (Alaska), lagoons in Baja California, the German/Danish Wadden Sea, the Golfe du Morbihan (France), British estuaries, and the White Sea (Western Russian Arctic). Diet Brent Geese are heavily herbivorous and mainly consume seagrass. They have relatively short necks and lack the ability to dive so can only reach plants at low tide or in shallow water. Interestingly, during breeding season the geese will consume a wide range of plant species but show a strong preference for Zostera species throughout non-breeding seasons due to the high digestibility and nutritional value compared to other options. They have been observed eating both the leaves and rhizomes of the plants. Importance of seagrass for Brent Goose populations As mentioned previously, Brent Geese rely heavily on seagrass during their migrations. This can be seen in population trends. In the 1930s, Zostera species across the North American coast were heavily affected by wasting disease and there was a significant population decline. At the same time, a steep decline in Brent Goose population was also observed on both sides of the Atlantic, with estimates ranging from 75 – 90% of populations lost. During the 1950s, there was a good recovery of seagrass beds in the areas previously affected, which was followed by a recovery of Brent Goose populations from around 15,000 to over 100,000. Similar smaller scale events like this have been observed, showing just how important healthy seagrass meadows are for species like the Brent Goose that rely so heavily on them. Are Brent Geese bad for seagrass restoration? It could be argued that Brent Geese are bad for seagrass and bad for seagrass restoration due to their consumption of the plants. However, there is a bit more to it than that. Seagrass provides services for many species, and a food source is one of those. Anecdotally, there have been instances where restoration has occurred only for geese to come along and eat all of the freshly planted shoots, which really isn’t ideal. In the scientific literature, there is mixed evidence about how much the geese will consume and how this affects the meadow’s health, which makes it difficult to quantify their impact. Some research notes that the percent the geese eat out of the whole meadow is actually quite small and a healthy meadow should have no issue recovering from any damage. The geese could even be useful in seagrass restoration. They tend to only be seen where food is available and as such are an indicator species for the health of an ecosystem. Like all birds, they are useful for their ability to spread nutrients and seeds through their faeces, helping to spread plant species more widely than they would on their own. Additionally, they are an important food source for predators such as foxes and raptors in their Arctic breeding grounds. Brent Geese, like any other species using seagrass, are carrying out behaviours that have evolved over thousands of years. Therefore, the question of whether geese are bad for seagrass restoration is not a straightforward one. What do you think? Sources: Ganter, B. (2000). Seagrass ( Zostera spp.) as food for brent geese ( Branta bernicla ): an overview. Helgoland Marine Research, 54(2–3), 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s101520050003 Find out more the role that seagrass plays for migratory birds here.