Seagrass Watch & Restoration Update – North Wales

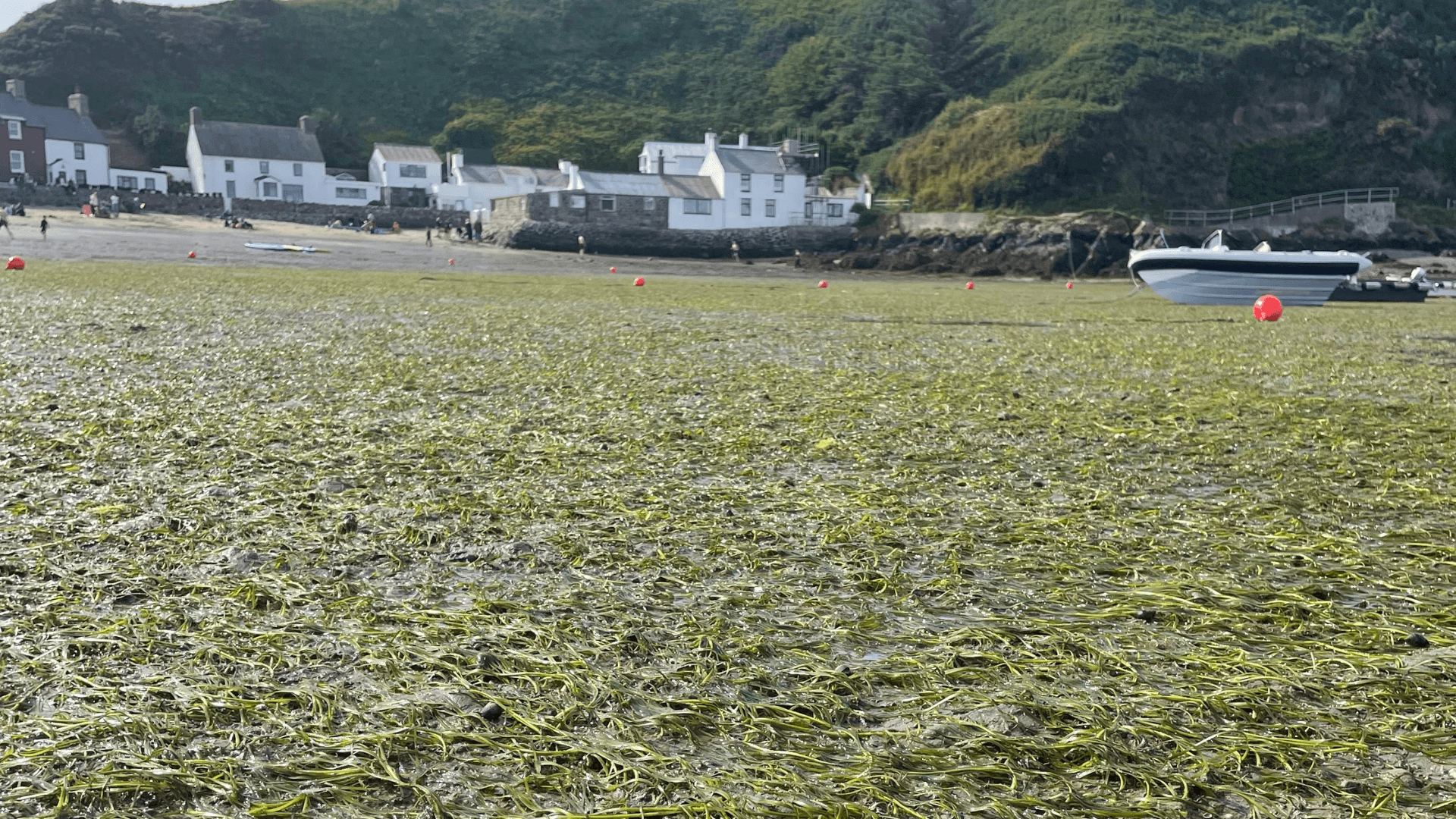

Earlier this year, Project Seagrass welcomed Rhys Bowen to the team to support our work in North Wales as part of the Seagrass Ocean Rescue North Wales programme. This follows on from Rhys’ involvement in the programme during 2024 where we worked as one of the Marine Futures Interns at our Seagrass Ocean Rescue partner, the North Wales Wildlife Trust. Rhys splits his time between Project Seagrass and North Wales Wildlife Trust. In this blog article Rhys reflects on recent seagrass monitoring he has been involved with in North Wales: Over the past few months, I’ve had the privilege of monitoring several key seagrass meadows and restoration sites across North Wales. These meadows, both old and new, play a vital role in our national marine conservation efforts. Seagrass Watch at Porthdinllaen, Llyn Peninsula In May, with the help of Dylan and Reece from North Wales Wildlife Trust, I conducted monitoring at our longstanding seed donor site in Porthdinllaen. We used the internationally recognised Seagrass Watch protocol which has been implemented at this meadow since 2015 and follows a rigorous, standardised approach. Using 50 cm² quadrats along three fixed transects, I collected data every 5 meters on: Seagrass cover. Epiphyte and algal presence. Average leaf lengths. This consistent monitoring at the same locations allows us to track changes in seagrass health over time and helps inform both conservation and restoration strategies. Seagrass meadow at Porthdinllaen. Photo Credit Rhys Bowen Project Seagrass Seagrass Watch monitoring at Porthdinllaen. Photo Credit Rhys Bowen Project Seagrass Restoration Efforts on Ynys Môn (Anglesey) As the Seagrass Ocean Rescue programme entered its fourth year, we continue to strive towards our goal to plant Zostera marina over an area of ten hectares across North Wales between 2022 and 2026. This year, at Penrhos and Penrhyn on Anglesey, we planted nearly 1 million seagrass seeds using two methods: The DIS (Dispenser Injection Seeding) technique. A manually powered seeding machine, developed by The Fieldwork Company designed to efficiently distribute mud-seed mixtures over large areas. Both methods have proved effective and the machine quickly won fans among our volunteers! Of which, none of this would be possible without the incredible support from our community groups, dedicated local volunteers, and the amazing Ocean Rescue Champions at the North Wales Wildlife Trust. Massive thanks to everyone who braved the weather and mud with us! As someone who is new to restoration, it was eye-opening to be a part of this ongoing work and witness the precision and care that goes into giving these tiny seeds the best chance of developing into healthy adult plants and meadows. First Signs of Growth In late June over the spring tides, I returned to Holyhead Bay with volunteers to assess the seagrass we had planted out in spring. We used 1m² quadrats to count seagrass shoots and measure leaf length and epiphyte coverage withing our planting plots. Following this period of monitoring I’m thrilled to report: Seagrass is growing across nearly all our planted plots. Shoots from both planting methods (DIS and Seeding machine) have emerged. Some leaves have already reached lengths of 12 cm and appear healthy. Monitoring will continue throughout the year alongside collection of environmental data. This will continue to inform and support our restoration work. The Seagrass Ocean Rescue team would like to thank the partners and volunteers for their continued support. Keep an eye out for more opportunities to get involved by signing up to our newsletter! Seagrass Watch Monitoring in Porthdinllaen

The Sea Hare: Creatures that call seagrass home

In a new blog series, our Conservation Trainee Abi David explores some of the amazing creatures that call seagrass meadows their home. Sea hares are odd looking creatures. They are mostly soft bodied but have a small internal shell, which separates them from their close relatives – sea slugs. The sea hare gets it name from the two rhinophores sticking out from the top of the head as they look like the ears of hares. However, these appendages aren’t used for hearing, but for taste and smell. A sea hare’s favourite snack is seaweed, but they also eat seagrass. Interestingly, the colour of the seaweed species most prominent in their diet influences the colour of the sea hare individual, for example: diets made from mostly sea lettuce will lead to a green body colour and reddish-maroon sea hares will be eating mostly red seaweeds. Sea Hare on seagrass. Photo Credit Lewis M Jefferies A Sea Hare within an Orcadian seagrass meadow. Photo Credit Lewis M Jefferies When threatened, they can produce a cloud of ink which the sea hare can hide in to confuse predators. Scientists have found that this ink has antibacterial properties, thought to be useful in healing wounds and combating harmful bacteria. Additionally, they can produce a slime on their skin which makes the sea hare less tasty and puts predators off from eating it. Sea hare species can range from 2 to 70cm, but the ones found around the UK – Aplysia punctata or dotted sea hare – are on the smaller size of 7 – 8cm and can be found throughout the year in rock pools and shallow waters. They lay their eggs in long string-like structures attached to seagrass, with the seagrass meadow acting as a nursery environment when the eggs hatch. They are hermaphrodites, meaning individuals have both male and female mating organs. Despite this, they still reproduce with others, usually in a line with multiple individuals. Sea Hares in seagrass As well as seaweeds, sea hares will consume seagrasses too. As with many marine species, seagrass meadows provide an important nursery habitat. By attaching developing eggs to seagrass leaves, the eggs are protected from strong currents and predators, as well as providing a food source for newly hatched sea hares. Some species, such as the Phyllaplysia taylori or eelgrass hare, live solely on seagrass. Evidence has shown presence of sea hares increases seagrass productivity as a result of grazing on epiphytes on the leaves. A build-up of too many epiphytes will block the leaves ability to photosynthesize, so these little creatures can be very handy for us seagrass scientists! Sea Hare (with egg strings) on a blade of seagrass. Photo credit Lewis M Jefferies But do sea hares benefit society? Yes! They form an important part of diets around the world. For example, in Hawaii, people wrap the sea hare in to leaves and cook it in an underground oven, called an imu. In the Philippines, egg strands, known as lokot, are eaten raw with vinegar and spices. Samoa, Kiribati and Fuji also have sea hares as part of the traditional diet. Often it is women that will go out and collect the sea hares at low tide on mudflats and seagrass meadows and then sell them at markets, so sea hares have an important economic benefit to these societies too. For further information about how grazers such as the sea hare are beneficial to seagrass, look at this article.