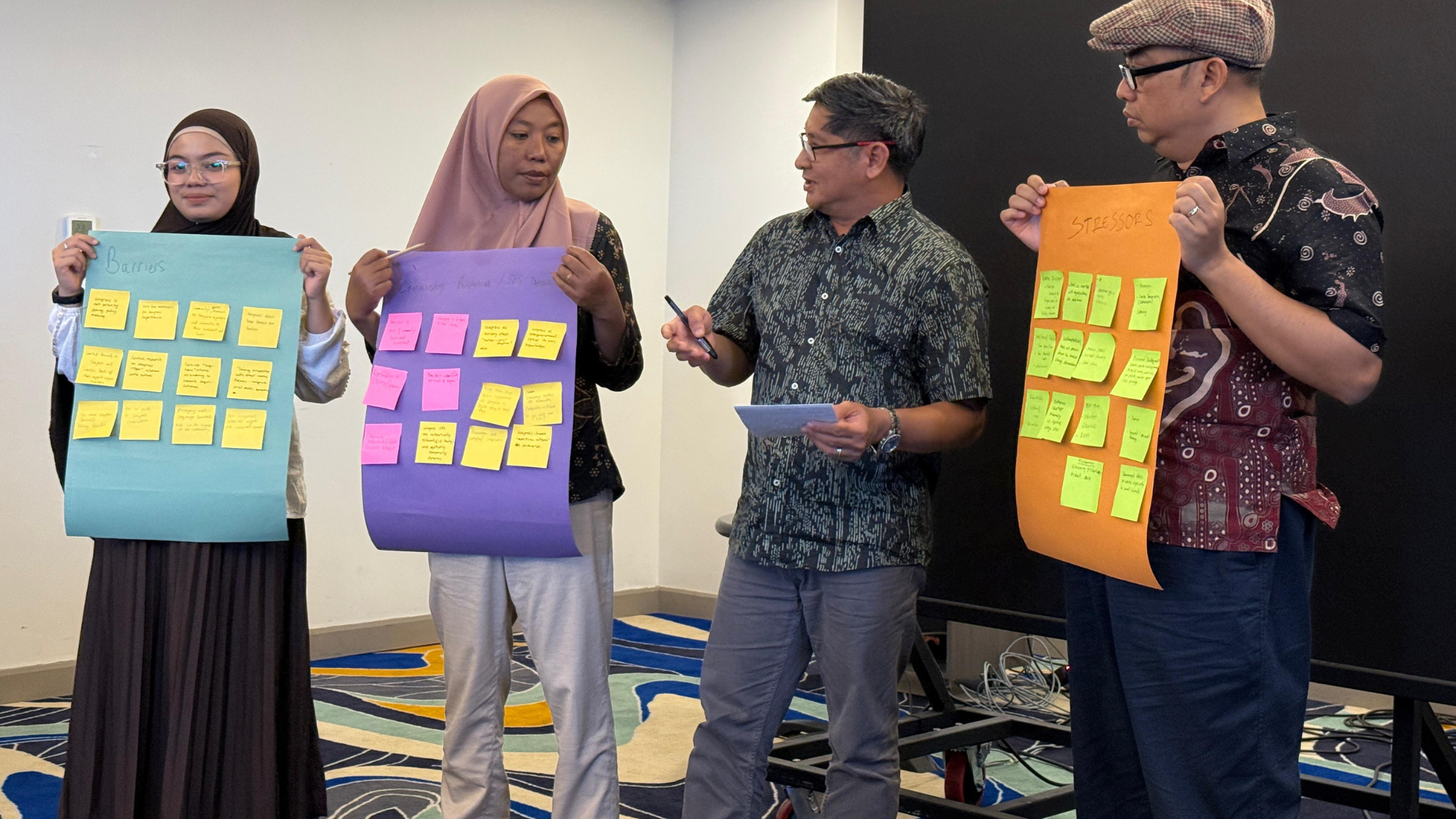

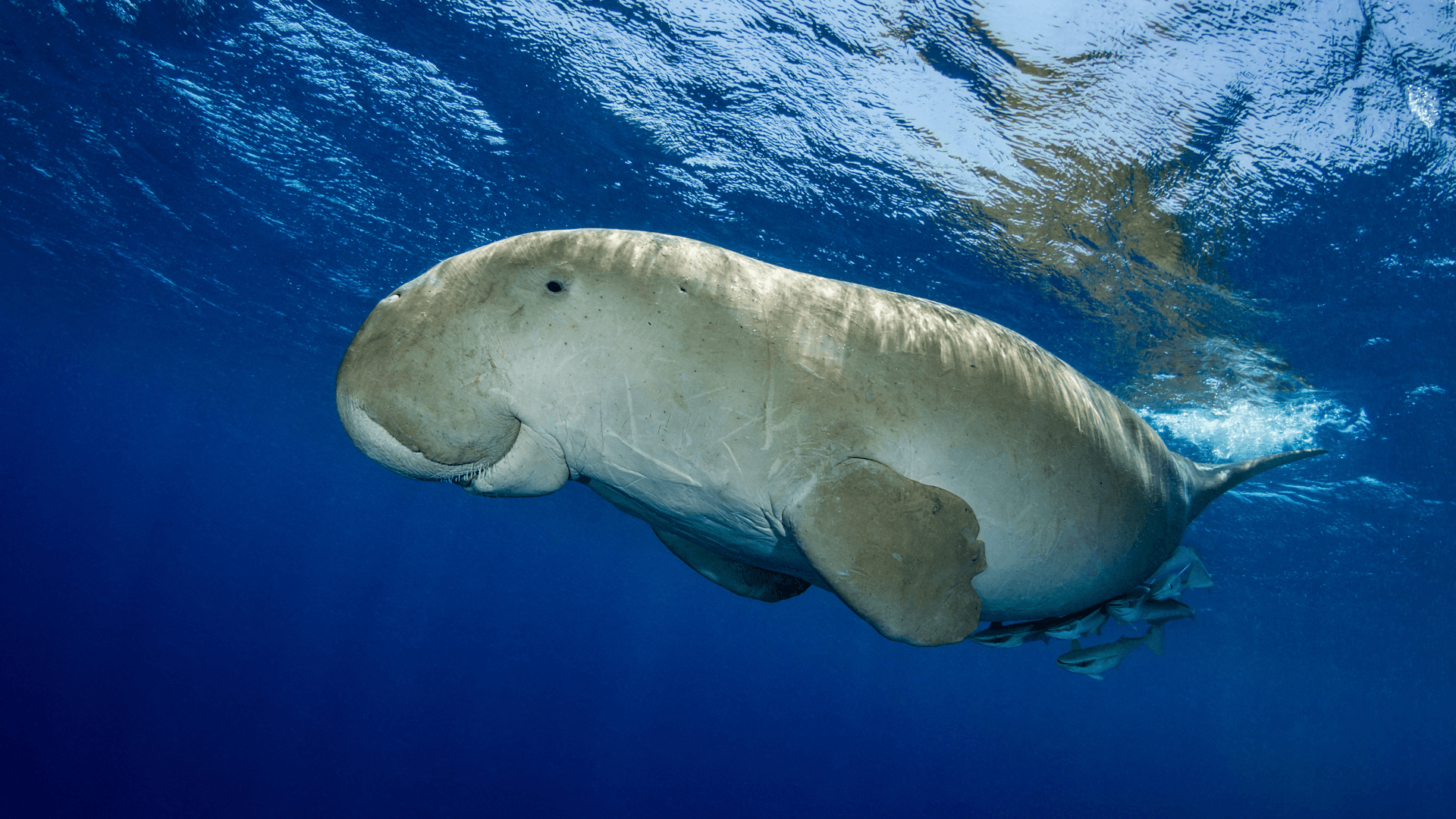

Seaweed farming is a rapidly expanding global industry. As a food resource, it has high nutritional value and doesn’t need fertilisers to grow. Seaweed provides valuable habitats for marine life, takes up carbon and absorbs nutrients, plus it helps protect our coastlines from erosion. Usually, seaweeds grow on hard, rocky surfaces. Yet, to farm seaweed, potential areas need to be easily accessible and relatively sheltered. This is where seaweed can grow with limited risk of being dislodged by waves. Seaweed farms in Asia, in countries like China and Indonesia, are responsible for more than 95% of global seaweed production. Seaweed farms, particularly those in Southeast Asia, are commonly in the very same environments where seagrass meadows thrive. Competition for resources ensues. Evidence shows that tropical seaweed farms, when placed in or on top of tropical seagrass meadows leads to a decline in the growth and productivity of seagrass. There is also evidence that seaweeds outcompete seagrasses in cooler waters, especially when nutrients in the water are very high. Despite negative interactions, such as shading, between seaweed and seagrass, some scientists now advocate for a global expansion of seaweed farming in areas where seagrass grows. This call, comes at a time when seagrass global initiatives are trying to stem seagrass loss. Efforts are underway to expand these habitats to their once extensive range to help fight climate change and biodiversity loss. Seagrass meadows are a crucial store of carbon, providing habitats for a wide array of animals. Why farm seaweed on top of seagrass? The reason that some scientists are advocating for farming seaweed in seagrass is that their research claims that the presence of seagrass reduces disease causing bacterial pathogens by 75%. A major win for a relatively low tech industry where seaweed disease outbreaks hinder production. These scientists are not the only ones advocating for seaweed production at scale. Global conservation charities, like World Wildlife Fund and The Nature Conservancy, as well as the Earthshot prize launched by Prince William all support seaweed cultivation programmes in areas likely to contain abundant seagrass. However, together with other scientists, we have argued in an academic response in the journal PNAS that their claim is premature. We are concerned that, without appropriate management, these seaweed programmes threaten marine biodiversity and the benefits that humans get from the ocean. Despite historic and globally widespread seaweed cultivation, effects on seagrass have mostly been ignored. Where studies exist, effects have been negative for seagrass, its ability to capture carbon, and the diverse animals that call it home. Entanglement of migratory animals, such as turtles and dugong with seaweed also needs wider consideration. This is especially the case given new legal frameworks to protect their habitat, and there is ongoing concern for these species being killed by seaweed farmers. The equity of coastal fishing grounds also comes into question, as communities that use seagrass for fishing are most likely to lose access. Conservation charities advocate for tropical seaweed farms for good reason. This is to improve community resilience in the face of degrading coral reefs and overfishing. While projects mostly have the best intentions, they often don’t consider cascading unintended consequences, nor the equity of the whole community. In reality, seaweed farm placement is effectively akin to ocean grabbing (the act of dispossession or appropriation of marine resources or spaces) with farmers winning on a “first come, first serve” basis, despite not owning the seabed. Some seagrass meadows in Zanzibar, Tanzania, have recovered since seaweed farms have been removed. GoogleEarth Sustainable standards If seaweed farming is to be expanded, standards for sustainability must be upheld and strengthened. In 2017, a sustainable seaweed standard was launched by the Aquaculture and Marine Stewardship Councils. But few tropical seaweed farms meet the criteria outlined in this standard due to known consequences that affect seagrass (rightly defined in the standard as vulnerable marine habitats) and likely negative effects on endangered species, like dugong, that frequent seagrass habitats. Seaweed cultivation strategies have mixed evidence for long-term success. In Tanzania, many farmers have abandoned the industry due to low monetary rewards compared to the investments they put in, and some evidence suggests that the activity reduces income and health, particularly for women. Where seaweed cultivation has been implemented to reduce fishing pressure, it has instead increased (and often just displaced) fishing activity. Given the rapidly increasing threats faced by tropical marine habitats despite the role they play in climate resilience, understanding trade-offs prior to large scale expansion of seaweed farming is a priority. To reduce further any negative effects, international programmes and research advocating for large-scale seaweed farms need to align more readily with the seaweed standard. More information: This article was published in The Conversation Jones. et al, Risks of habitat loss from seaweed cultivation within seagrass, PNAS (2025). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.242697112 Seaweed farms are often placed on top of seagrass meadows. Niels Boere/flickr A women prepares seaweed ropes for deployment in the Wakatobi, Indonesia. Benjamin Jones/Project Seagrass