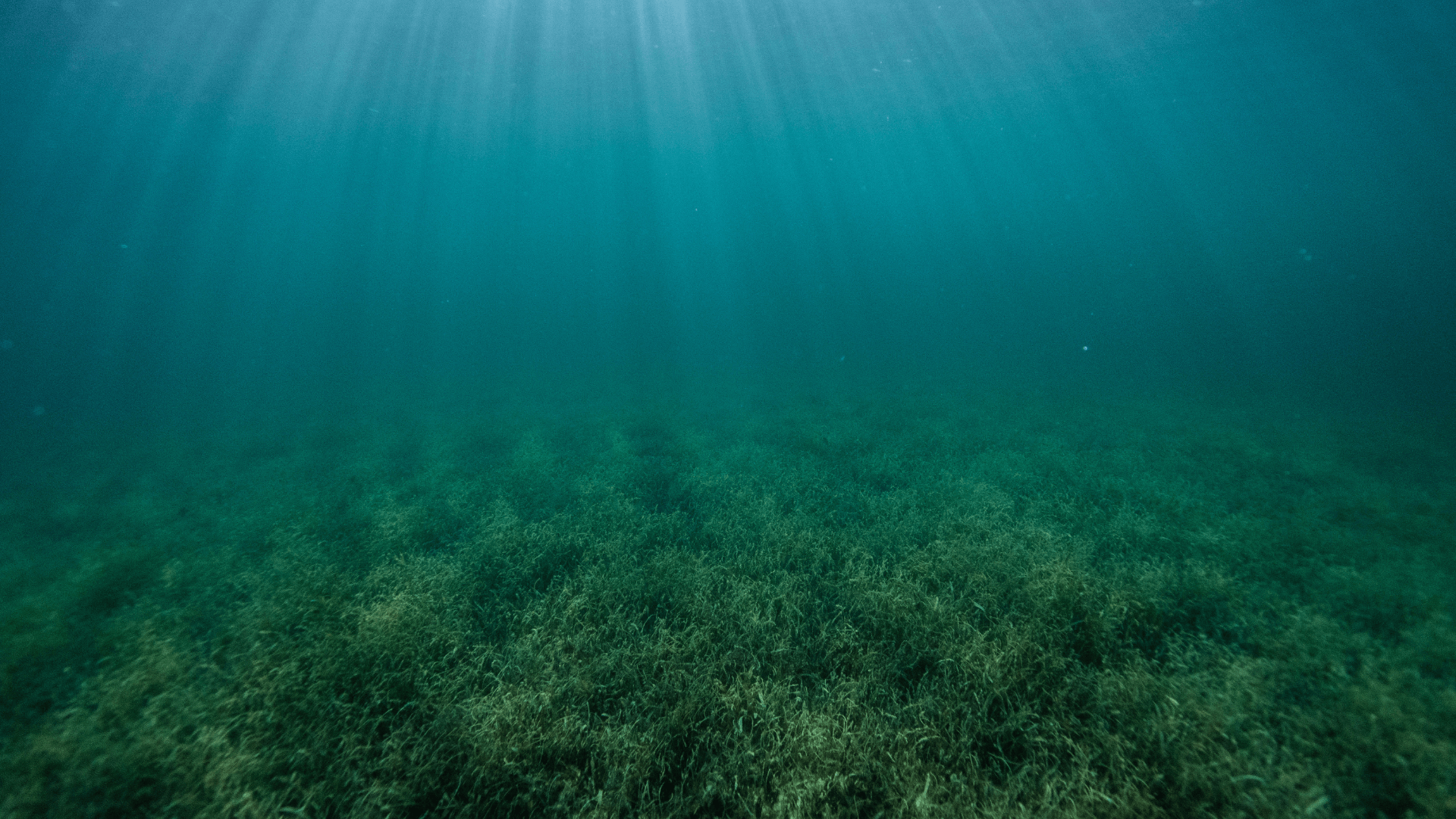

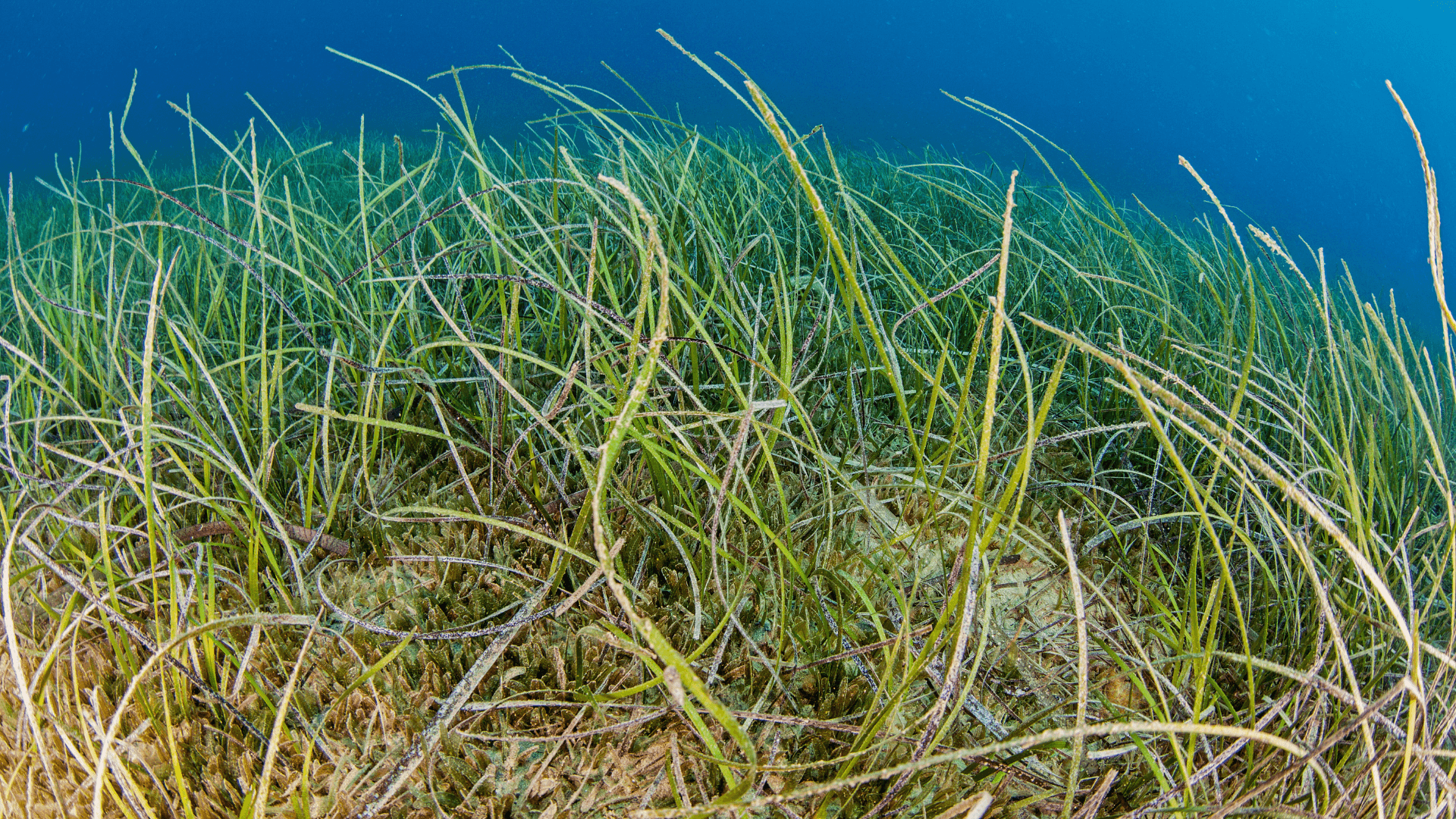

For millennia, humans lived as hunter-gatherers. Savannas and forests are often thought of as the cradle of our lineage, but beneath the waves, a habitat exists that has quietly supported humans for over 180,000 years. Archaeological evidence suggests that early humans migrated along coasts, avoiding desert and tundra. So, as Homo spread from Africa, they inevitably encountered seagrasses – flowering plants evolved to inhabit shallow coastal environments that form undersea meadows teeming with life. Our recently published research pieces together historical evidence from across the globe, revealing that humans and seagrass meadows have been intertwined for millennia – providing food, fishing grounds, building materials, medicine and more throughout our shared history. Our earliest known links to seagrass date back around 180,000 years. Tiny seagrass-associated snails were discovered in France at Paleolithic cave sites used by Neanderthals. Too small to be a consequence of food remains, these snails were likely introduced with Posidonia oceanica leaves used for bedding – a type of seagrass found only in the Mediterranean. Neanderthals didn’t just use seagrass to make sleeping comfortable – 120,000 year old evidence suggests they harvested seagrass-associated scallops too. A bountiful supply of food Seagrass meadows provide shelter and food for marine life, such as fish, invertebrates, reptiles and marine mammals. Because they inhabit shallow waters close to shore, seagrass meadows have been natural fishing grounds and places where generations have speared, cast nets, set traps and hand-gathered food to survive and thrive. Long before modern fishing fleets, ancient communities recognised the value of these underwater grasslands. Around 6,000 years ago, the people of eastern Arabia depended on seagrass meadows to hunt rabbitfish – a practice so prevalent here that remnants of their fishing traps are still visible from space. Historic stone fish traps designed to capture seagrass associated fish as the tide retreats. Photos Benjamin Jones Satelite image Apple Maps Seagrass meadows have even been directly harvested as food. Around 12,000 years ago, some of the first human cultures in North America, settling on Isla Cedros off the coast of Baja California, gathered and consumed seeds from Zostera marina, a species commonly called eelgrass. These seeds were milled into a flour and baked into breads and cakes, a process alike to wheat milling today. Further north, the Indigenous Kwakwaka’wakw peoples, as far back as 10,000 years ago, developed a careful and sustainable way of gathering eelgrass for consumption. By twisting a pole into the seagrass, they pulled up the leaves, and broke them off near the rhizome – the underground stem that is rich in sugary carbohydrates. After removing the roots and outer leaves, they wrapped the youngest leaves around the rhizome, dipping it in oil before eating. Remarkably, this method was later found to promote seagrass health, encouraging new growth and resilience. Today, seagrass meadows remain a lifeline for coastal communities, particularly across the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Here, fishing within seagrass habitats is shown to be more reliable than other coastal habitats and women often sustain their families by gleaning – a fishing practice that involves carefully combing seagrass meadows for edible shells and other marine life. For these communities, seagrass fishing is vital during periods when fishing at sea is not possible, for example, during tropical storms. When seagrasses returned to the sea around 100 million years ago, they evolved to have specialised leaves to tolerate both saltwater submergence and periods of time exposed to the sun during tidal cycles. This allowed seagrasses to flourish across our coastlines, but also made them useful resources for humans. Mudbricks discovered at the Malia Archaeological Site, Crete, contain remains of seagrass leaves. Olaf Tausch Wikimedia Commons Seagrass leaves, once dry, are relatively moist- and rot-proof – properties likely discovered by ancient civilisations when exploring the uses of plants for different purposes. Bronze age civilizations like the Minoans, used seagrass in building construction, reinforcing mudbricks with seagrass. Analysis of these reveal superior thermal properties of seagrass mudbricks compared to bricks made with other plant fibres – they kept buildings warmer in winter and cooler in summer. These unique properties may have been why early humans used seagrass for bedding and by the 16th century, seagrass-stuffed mattresses were prized for pest resistance, requested even by Pope Julius III. Three hundred year old seagrass thatched roof from the island of Læsø, Denmark. Jack Fridthjof/Visitlaesoe By the 17th century, Europeans were using seagrass to thatch roofs and insulate their homes. North American colonialists took this knowledge with them, continuing the practice. In the 19th century, commercial harvesting of tens of thousands of tonnes of seagrass began across North America and northern Europe. In the US, Boston’s Samuel Cabot Company patented an insulation material called Cabot’s “Quilt”, sandwiching dried seagrass leaves between two layers of paper. These quilts were used to insulate buildings across the US, including New York’s Rockefeller Center and the Capitol in Washington DC. A legacy ecosystem – and a living one The prevalence of seagrass throughout human civilisation has fostered spiritual and cultural relations with these underwater gardens, manifesting in rituals and historical customs. In Neolithic graves in Denmark, scientists found human remains wrapped in seagrass, representing a close connection with the sea. “If we have depended on seagrass for 180,000 years—for food, homes, customs—investing in their conservation and restoration is not just ecological, it’s deeply human,” said Project Seagrass’ Chief Conservation Officer Dr Benjamin Jones. “They were not just background scenery — they were practical, valuable, and even life-saving. They’re also solutions hiding in plain sight for things like food resilience — habitats that offer communities today a lifeline in times of need.” Our new research tells us that seagrass meadows are not just biodiversity hotspots or carbon storage systems. They are ancient human allies. This elevates their value beyond conservation – they’re repositories of cultural heritage and traditional knowledge. They were practical, valuable, and deeply integrated into human cultures. We have depended on seagrass for 180,000 years – for food, homes, customs – so investing in their conservation and restoration is not just ecological, it’s deeply human.