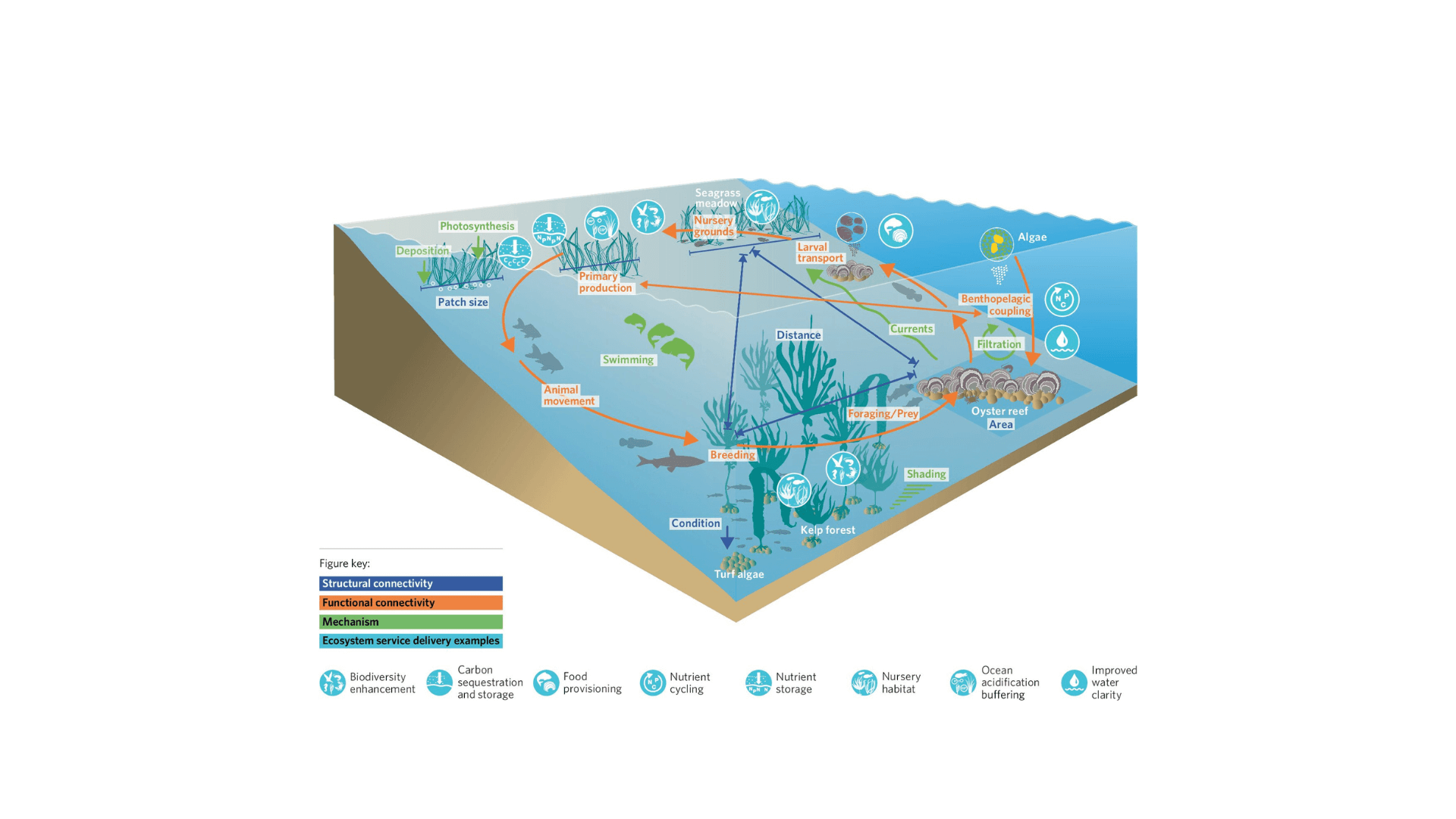

Scientists warn that the future of our oceans and climate goals depends on reconnecting the ecological threads that hold coastal habitats together. A new study, launched at the International Seascape Symposium II at ZSL (Zoological Society of London), and published to align with UN Ocean Decade Conference represents two years of work by an international team led by the University of Portsmouth, with support from ZSL and University of Edinburgh. It delivers the most comprehensive report to date on how coastal habitats in temperate regions function not in isolation, but as interconnected systems—a concept known as ecological connectivity. “Coastal habitats like oyster reefs, salt marshes, kelp forests, and seagrass meadows are often treated as separate entities in policy and restoration, but in reality, they are tightly bound together by the flows of water, life, and energy,” said lead author Professor Joanne Preston, Institute of Marine Sciences at the University of Portsmouth. “To meet our global climate and biodiversity targets, we need to restore the entire seascape.” Published in npj Ocean Sustainability to coincide with World Ocean Day and the midpoint of the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, the paper makes the case that reconnecting these habitats is fundamental to repairing the damage caused by centuries of degradation, and to achieving international targets under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, Paris Agreement, and the Sustainable Development Goals. Schematic figure illustrating how structural connectivity, functional connectivity, mechanisms and ecosystem service delivery relate. Examples of structural connectivity are denoted by blue arrows and font, functional connectivity by orange arrows and font and mechanisms are indicated by green arrows and font. The light blue icons provide examples of ecosystem services delivery enhanced by the connectivity across seascape habitats. Credit: npj Ocean Sustainability (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s44183-025-00128-3 Conceptual diagram of how ecosystem services from a restored and connected seascape underpins the interrelationships between climate mitigation, biodiversity and human wellbeing. Credit npj Ocean Sustainability 2025 Dr. Philine zu Ermgassen, Changing Oceans Group, University of Edinburgh, said, “Ecological connectivity allows organisms, nutrients, sediment, and energy to move between different marine habitats. These exchanges drive crucial ecosystem services—from carbon storage to water filtration, coastal protection to fishery productivity.” The research compiles evidence from global temperate regions showing that habitat co-location consistently improves ecosystem service delivery. In California, for example, seagrasses grow more robustly when adjacent to oyster reefs. On the U.S. East Coast in the Chesapeake Bay region, oyster beds dramatically increase water clarity and nutrient removal. Additionally, in New Zealand, kelp-derived carbon boosts fish populations in fjords. “Connected habitats are more productive, more resilient, and more beneficial to people,” said co-author Alison Debney, Estuaries and Wetlands Program Lead at ZSL. “Restoring isolated patches isn’t enough. We need to think like the sea—fluid, linked, dynamic— and we need to act at scale.” In response, the authors propose a formal definition of seascape restoration: the concurrent or sequential restoration of multiple habitats to rebuild functional, resilient, and connected marine ecosystems. They call for a shift away from “feature-based” conservation approaches toward holistic, connectivity-based planning. This includes updating marine protected area (MPA) frameworks, development policies, and restoration funding criteria to account for the value of ecological links across habitats. “We are at a critical moment,” said Professor Preston. “The UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration and the Decade of Ocean Science give us the tools and momentum. But unless we restore the seascape as a whole—the full mosaic of habitats and their connections—we risk missing the targets set by policymakers.” The study outlines clear recommendations to policymakers, including: Mainstreaming seascape connectivity into climate and biodiversity policies Integrating restoration goals across land-sea interfaces Recognizing the role of connectivity in climate mitigation and adaptation Updating environmental assessments to evaluate ecosystem service delivery at the seascape scale Illustration of the role of connectivity in modulating ecosystem service delivery across the coastal seascape. Arrows relate to icons of the same color, with the arrowhead indicating the habitat in which the ecosystem service is enhanced through connectivity with the source habitat. Credit: npj Ocean Sustainability (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s44183-025-00128-3 “We need to view coastal habitats as interconnected systems,” said co-author Rosalie Wright, Blue Marine Foundation. “Our fragmented policy and regulatory approaches must transition to holistic, seascape-scale thinking. Addressing these barriers will enable the urgently needed recovery of our coastlines.” This work directly supports Target 2 of the Global Biodiversity Framework, which calls for at least 30% of degraded coastal and marine ecosystems to be under effective restoration by 2030, specifically enhancing connectivity and ecological function. The findings come amid growing concern over the collapse of marine habitats in temperate zones. Over the past two centuries, the U.K. alone has lost up to 95% of its oyster reefs, over 90% of its seagrasses, and vast expanses of saltmarsh. These losses jeopardize not only biodiversity but also carbon storage, fish stocks, and coastal protection. Restoring at scale and in a way that mirrors the ecological realities of the coast offers a powerful nature-based solution to the interlinked crises of climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution. As the world gathers momentum around ocean recovery, the message from the science is unequivocal: seascape-scale restoration is not optional. It is essential. More information: J. Preston et al, Seascape connectivity: evidence, knowledge gaps and implications for temperate coastal ecosystem restoration practice and policy, npj Ocean Sustainability (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s44183-025-00128-3