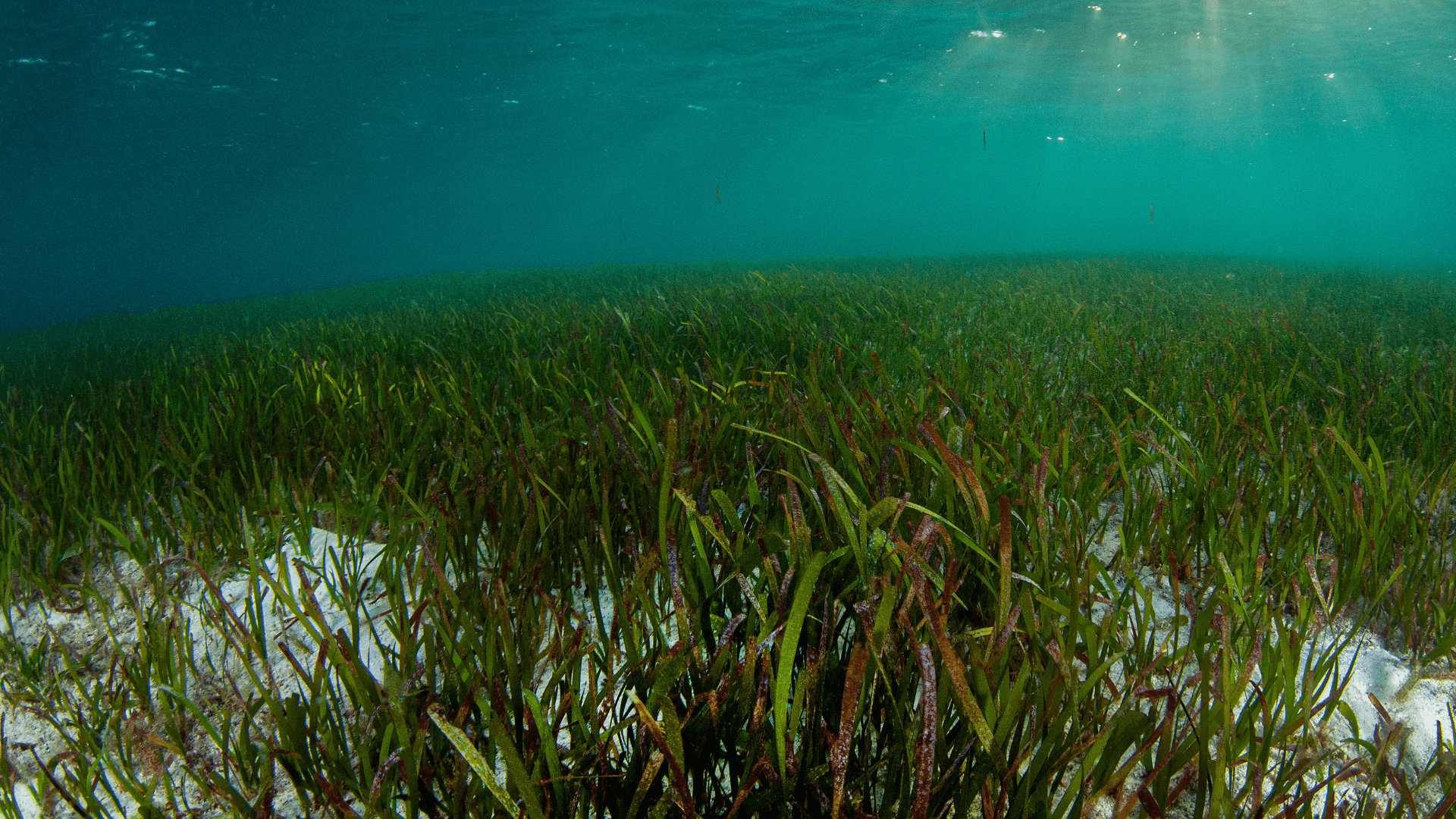

Jasper Brown, one of Project Seagrass’ Interns for the 2025-26 academic year and 3rd Year Student in BSc Zoology with Marine Zoology at Bangor University, explores the need for both active and passive restoration to secure a future for our important seagrass habitats. Marine ecosystems worldwide are under threat. Rising temperatures, ocean acidification, and water pollution are just a few of the key drivers in the decreasing quality of our marine ecosystems. Researchers have found that many aquatic species are shifting poleward at an average rate of 70 kilometres every decade (Melbourne-Thomas et al., 2021) – a vast response to changing conditions. Species such as the American Lobster, Cushion Star, and Humboldt Squid have nearly doubled their latitude range, showing the clear extent of this poleward shift in marine species (Pinsky et al., 2020). Why are they moving? One crucial reason is habitat loss. Seagrass meadows, coral reefs, and kelp forests are disappearing worldwide, reducing opportunities for biodiversity and removing essential nursery habitats for marine life. The solution is clear: we must conserve and restore. Across the globe, charities and organisations are embracing active restoration – direct interventions to rebuild habitats. The work consists of planting seagrass, reforesting mangroves, and coral Gardening. All of which provide crucial environmental benefits: large carbon sinks, coastal protection, and providing nursery habitats. Seagrass planting involves transplanting seeds and rhizomes near existing meadows (do Amaral Camara Lima et al., 2023). Coral gardening uses nurseries to grow coral fragments, which are later transplanted to reefs that support approximately 25% of all marine species (Rinkevich, 2014; Gallagher, 2025; Pacific Coastal and Marine Science Center, 2022). Mangrove reforestation involves planting seedlings along suitable coastlines (Zahra Farshid et al., 2022; Bimrah et al., 2022). These methods are being implemented worldwide, from the Persian Gulf in western Asia to the Firth of Forth in Scotland. Yet, challenges persist. Active restoration projects are costly, often relying on charitable donations and grants (Paling et al., 2009). Despite these hurdles, active restoration works, a recent review by Danovaro (2025), found an average success rate of 64% across 764 projects. Is active restoration enough? However, success depends on environmental conditions; water clarity, for example, is critical for seagrass survival due to photosynthesis requiring sufficient light. Declining clarity, driven by pollution, bottom trawling, and dredging, increases turbidity, which limits restoration efforts (Paling et al., 2009). This is where passive restoration comes in Passive strategies focus on removing environmental pressures and creating conditions for ecosystems to heal naturally. Examples include implementing policies to regulate fertilizer use and reduce nutrient runoff, as well as enforcing Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). These acts will reduce eutrophication in our waterways and lead to a more stable marine environment, leading to the eventual reduction in coral bleaching and seagrass meadow reduction. MPAs have been shown to restore ecosystem functions such as predation (Cheng et al., 2019), highlighting their critical role in maintaining biodiversity. Conclusion While MPAs are just one example, they perfectly highlight the value of passive restoration in its entirety. The greatest benefits come from integrating passive and active approaches. By enforcing regulations and establishing strict no-trawl zones, we can reduce nutrient loads and sedimentation. Through these efforts, our marine ecosystems will one day thrive again, meaning we get to see the animals and plants we so dearly care about. References Bimrah, K., Dasgupta, R., Hashimoto, S., Saizen, I., & Dhyani, S. (2022). Ecosystem Services of Mangroves: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of Contemporary Scientific Literature. Sustainability, 14(19), 12051. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912051 Bulmer, R. H., Townsend, M., Drylie, T., & Lohrer, A. M. (2018). Elevated Turbidity and the Nutrient Removal Capacity of Seagrass. Frontiers in Marine Science, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2018.00462 Cheng, B. S., Altieri, A. H., Torchin, M. E., & Ruiz, G. M. (2019). Can marine reserves restore lost ecosystem functioning? A global synthesis. Ecology, 100(4), e02617. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2617 Danovaro, R., Aronson, J., Bianchelli, S., Boström, C., Chen, W., Cimino, R., Corinaldesi, C., Cortina-Segarra, J., D’Ambrosio, P., Gambi, C., Garrabou, J., Giorgetti, A., Grehan, A., Hannachi, A., Mangialajo, L., Morato, T., Orfanidis, S., Papadopoulou, N., Ramirez-Llodra, E., & Smith, C. J. (2025). Assessing the success of marine ecosystem restoration using meta-analysis. Nature Communications, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57254-2 do Amaral Camara Lima, M., Bergamo, T. F., Ward, R. D., & Joyce, C. B. (2023). A Review of Seagrass Ecosystem services: Providing nature-based Solutions for a Changing World. Hydrobiologia, 850(12-13), 2655–2670. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-023-05244-0 Gallagher, M. (2025, August 24). What Ecosystem Services Do Coral Reefs Provide? – Green Packs. GreenPacks. https://greenpacks.org/what-ecosystem-services-do-coral-reefs-provide/ Melbourne-Thomas, J., Audzijonyte, A., Brasier, M. J., Cresswell, K. A., Fogarty, H. E., Haward, M., Hobday, A. J., Hunt, H. L., Ling, S. D., McCormack, P. C., Mustonen, T., Mustonen, K., Nye, J. A., Oellermann, M., Trebilco, R., van Putten, I., Villanueva, C., Watson, R. A., & Pecl, G. T. (2021). Poleward bound: adapting to climate-driven species redistribution. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-021-09641-3 Pacific Coastal and Marine Science Center. (2022, June 27). Role of Reefs in Coastal Protection | U.S. Geological Survey. Www.usgs.gov. https://www.usgs.gov/centers/pcmsc/science/role-reefs-coastal-protection Paling, Fonseca, M., Katwijk, M., & Keulen, van. (2009). Seagrass restoration. In Coastal wetlands: an integrated ecosystems approach. (pp. 687–713). Rinkevich, B. (2014). Rebuilding coral reefs: does active reef restoration lead to sustainable reefs? Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 7, 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2013.11.018 Zahra Farshid, Reshad Moradi Balef, Tuba Zendehboudi, Dehghan, N., Mohajer, F., Siavash Kalbi, Hashemi, A., Afshar, A., Tabandeh Heidari Bafghi, Hanieh Baneshi, & Amin Tamadon. (2022). Reforestation of grey mangroves (Avicennia marina) along the northern coasts of the Persian Gulf. Wetlands Ecology and Management, 31(1), 115–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-022-09904-1