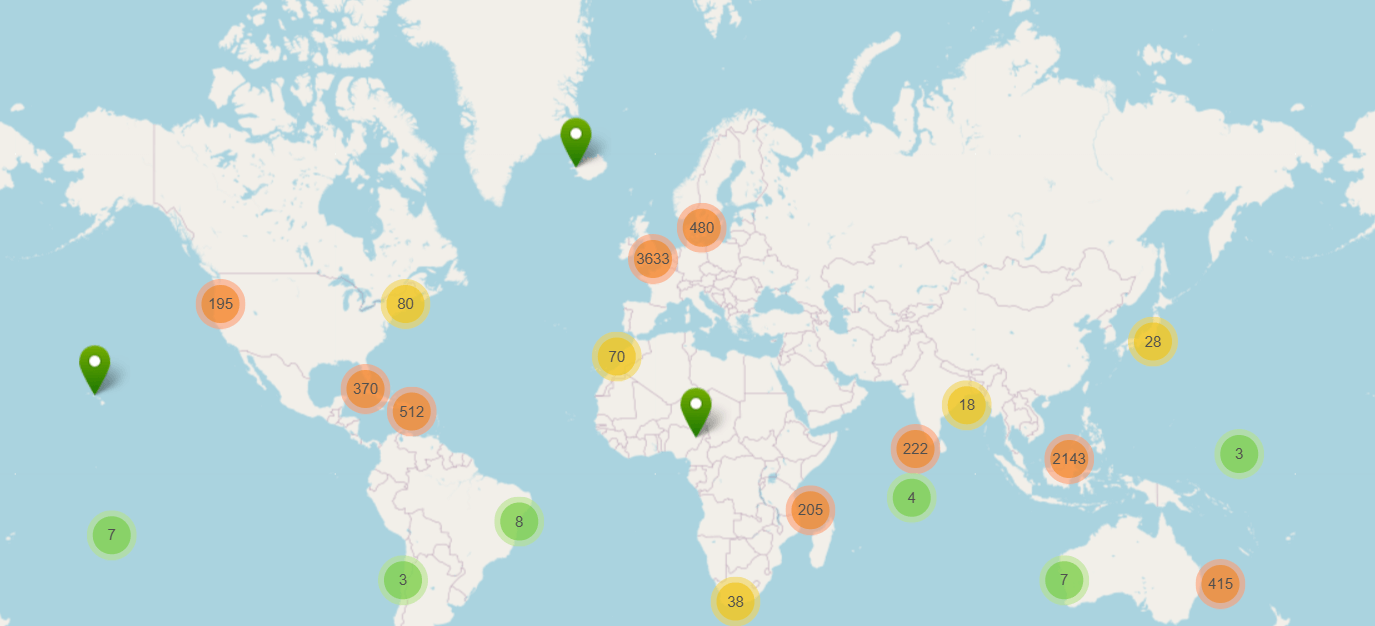

Our oceans and coasts are home to ecosystems that provide immense benefits to people, from food and livelihoods to carbon storage and coastal protection. In particular, seagrass meadows are archetypal social-ecological systems (SES), linking human well-being to ecosystem health. But to manage these systems effectively, we need access to both ecological data (such as habitat extent, biodiversity, or water quality) and social data (such as fishing activity, governance, or community use). In a new paper led by Uppsala University, Project Seagrass Chief Conservation Officer Dr. Benjamin Jones, joined forces with scientists from Sweden and the USA to explore how researchers and managers can better use open-access data to integrate these perspectives and improve decision-making. Why this data matters Over the past decade, the amount of freely available ecological and social data has exploded. From satellite-derived habitat maps to global fisheries datasets, there is now a wealth of information that could support more holistic approaches to conservation and management. Such data includes the likes of our very own SeagrassSpotter dataset. Yet, this opportunity comes with challenges. For many practitioners, the biggest barrier is knowing where to find relevant datasets and how to make sense of them in a way that reflects both the ecological and social dimensions of coastal systems. Without broad interdisciplinary training, it can be easy to feel overwhelmed by the sheer volume and complexity of open data sources. To address this challenge, we developed a workflow based on a social-ecological systems framework to help researchers systematically identify the types of variables they need (e.g., ecological, social, or governance-related) and guides the search for appropriate open datasets. The workflow was demonstrated using seagrass meadows in the Tropical Indo-Pacific, a region where millions of people depend directly on coastal ecosystems. This provides a strong test case for exploring how open data can inform both research and management and highlights just how much open-access information is already available, from global biodiversity repositories to socioeconomic databases, and how it can be assembled into a more complete picture of system dynamics. The study underscores the huge potential of open data to support inclusive and interdisciplinary approaches in coastal science. It allows researchers to explore ecological and social indicators side by side, ask new, cross-cutting research questions, support management decisions even in data-poor regions and facilitate collaboration across disciplines and geographies. However, there are important challenges. First, data can be patchy or biased, with strong coverage of biophysical variables but limited social or long-term monitoring data. Second, many datasets are coarsely aggregated or inconsistent in spatial and temporal coverage. Third, users often require specialised technical skills to access, harmonise, and analyse the data and finally, the “paradox of choice” means the sheer volume of available datasets can be overwhelming without a clear framework to guide selection. These limitations highlight the need for continued investment in training, better tools, and improved data-sharing practices. The paper also emphasises the importance of contributing data back into open repositories such as the Ocean Biodiversity Information System. By sharing primary data openly, researchers and practitioners not only enhance the value of their own work but also support a stronger, more connected global community. Project Seagrass is committed to this via its open access SeagrassSpotter database, and the newly launched SeagrassRestorer. This cultural shift towards open data sharing, proper attribution of data collectors, and incentivising contributions is essential if we are to unlock the full potential of open data in advancing coastal science and conservation. Frameworks like this provide a structured way of navigating the open-data landscape. By combining social and ecological variables, researchers and managers can move beyond siloed approaches to develop a truly integrated understanding of coastal systems. For seagrass meadows and other critical coastal habitats, this means being better equipped to anticipate change, design effective interventions, and ensure the long-term provision of ecosystem services that millions of people depend upon. In short: open data, when harnessed effectively, is a powerful tool for bridging science and society and for building more sustainable futures for our coasts.