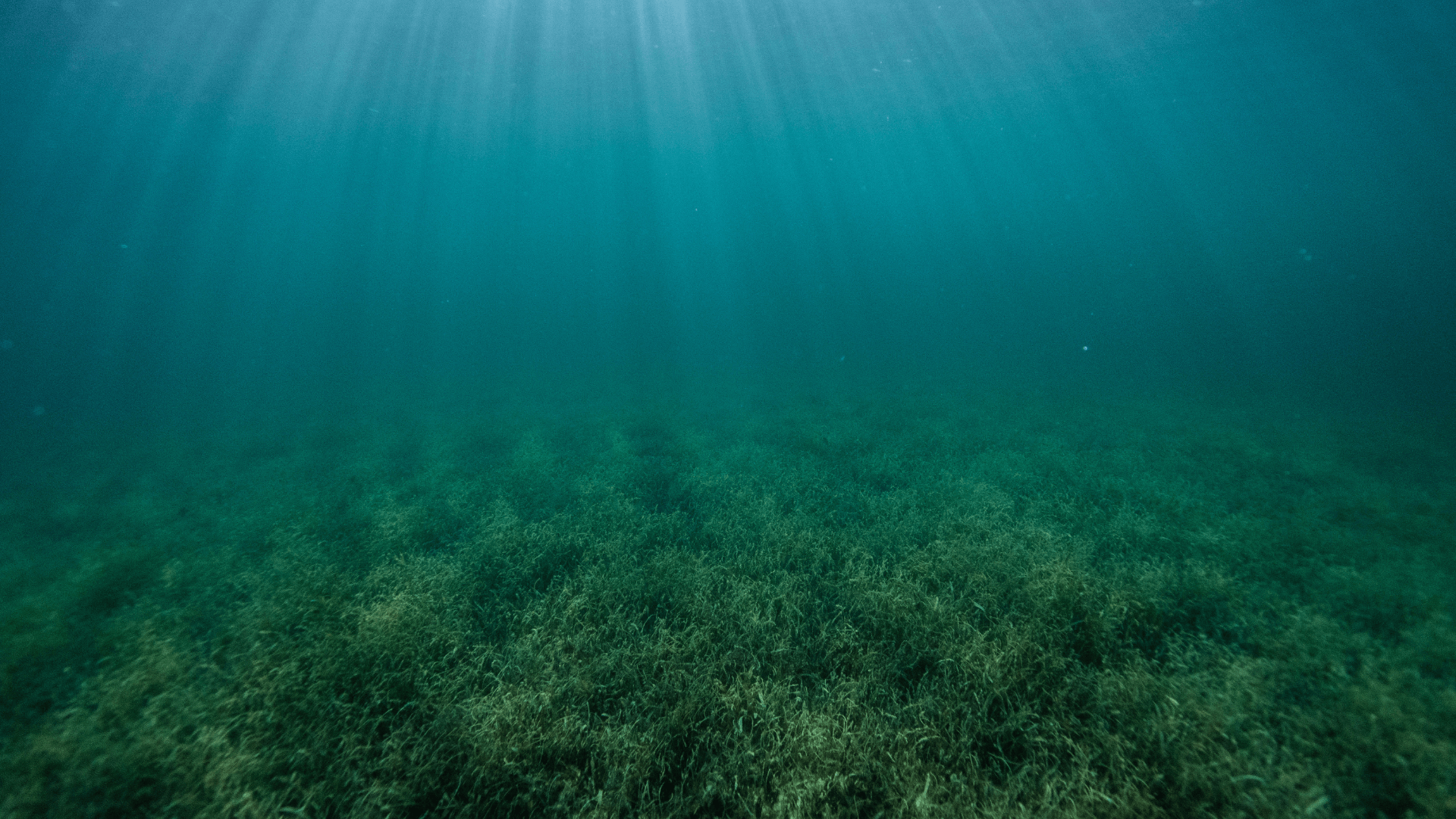

Seagrass meadows could be good for your health – yet they’re disappearing fast

The wellbeing benefits of nature are often linked to forests or habitats that support diverse pollinators. Spending time in green spaces reduces stress and anxiety, for example. By contrast, the benefits of the ocean are more commonly associated with fishing, exciting creatures such as whales and dolphins, or adventure watersports, rather than as a living system that directly supports human wellbeing. Yet growing scientific evidence shows that marine biodiversity is fundamental to the health of people, animals and the planet. The “one health” concept (a term now widely used by the World Health Organization) captures this connection by recognising that human health, animal health and environmental health are inseparable. Our new paper in the journal BioScience applies this idea to seagrass meadows for the first time. We argue that healthy coastal ecosystems such as seagrass meadows are not optional extras, but essential infrastructure for resilient societies. Coastal seas host some of the most biologically rich ecosystems on Earth. Kelp forests, oyster reefs, saltmarshes and seagrass meadows form the foundation of complex food webs that support fisheries, regulate water quality and protect shorelines. These habitats influence everything from food security and livelihoods to exposure to pollution and disease. Take seagrass meadows as one example. These underwater flowering plants stabilise sediments, reduce wave energy and filter nutrients from coastal waters. The benefits ultimately reduce coastal flooding and make the environment cleaner. They also support young fish and invertebrates that later populate offshore fisheries. Seagrass and water quality exist in a delicate balance. When the quality becomes too poor the seagrass becomes less abundant, and it’s then less able to act as a filter. This further exacerbates the water quality problems with implications for fish and other wildife. Similar patterns are seen when kelp forests collapse or shellfish reefs are lost. This is why we need better recognition for the important roles these habitats play. Marine biodiversity also helps regulate the Earth’s climate. Coastal habitats such as seagrass capture and store carbon and can reduce the negative effects of storms and flooding. While saving these ecosystems can’t replace the need to cut greenhouse gas emissions, their loss can accelerate climate impacts at local and regional scales increasing risks to coastal communities. Despite their importance, many marine ecosystems have been severely degraded. Pollution, overfishing, coastal development and warming seas have reduced biodiversity along coastlines around the globe. These losses are rarely visible to the public as they’re hard to see. This is because these losses occur underwater and gradually. Yet their consequences are increasingly felt through declining fisheries, poorer water quality and greater vulnerability to extreme weather. These factors all ultimately affect our health and wellbeing. Our new paper argues that restoring marine biodiversity requires a shift in how success is measured. Conservation and restoration efforts are often judged by the amount of hectares of habitat planting planted or short-term project outcomes. While these metrics are easy to calculate, they can obscure the real goal: the recovery of ecological function and long-term resilience. Biodiverse seagrass habitats have huge value to fisheries, from industrial fishing vessels to communities fishing by hand. Richard Unsworth A collaborative approach This is where the one health perspective becomes particularly valuable. By linking environmental condition to human and animal health, it encourages collaboration across disciplines that rarely interact. Coastal management, public health, fisheries policy and climate adaptation are often treated separately yet they all depend on the same underlying ecosystems. Examples from around the world show that biodiversity can do miraculous things, such as seagrass meadows trapping pathogens, reducing harmful bacteria in coastal waters that kills corals and contaminates seafood. That’s nature directly buffering human and animal health. We also know that when habitat is degraded and lost, it displaces associated wildife. This can lead to greater interactions between wild and farmed animals. In the case of seagrass loss, typically we know that geese become displaced to farmland to graze. This has the potential to increase interactions with farmed animals and could enhance spread of diseases such as bird flu. Recovery of our ocean habitats and the wildlife, plants and microbes that live there is possible. Where water quality improves and physical disturbance is reduced, marine habitats can rebound, bringing measurable benefits for biodiversity fisheries and coastal protection. Importantly, the benefits then extend to people – cleaner water, a more affable environment and better, more abundant food. However restoration of these habitats alone cannot compensate for ongoing damage. Protecting what remains is consistently more effective and less costly than rebuilding ecosystems after they collapse. Marine biodiversity may feel distant from everyday life but it quietly supports many of the systems that societies depend on. Recognising oceans and coasts as part of our shared health system rather than as separate from it could transform how we manage and value the marine environment. In a changing climate, this shift may prove essential not only for nature but for our own resilience. This article was originally published in The Conservation.

Can seagrass survive extreme heat? Exploring how different species withstand elevated water temperatures

Extreme heat can have a devastating effect on seagrass, but new research from Edith Cowan University (ECU) could shape how these vitally important marine ecosystems are managed and restored. In separate studies carried out on both the west and east coasts of Australia, researchers have investigated how seagrasses stand up to marine heat waves and prolonged ocean warming. Executive Dean of ECU’s School of Science, Professor Marnie Campbell, conducted the research during her time at Central Queensland University. She noted that insights into how different intertidal species respond to elevated water temperatures are critical for informing future seagrass management. “The outcomes demonstrate that the way we protect and restore seagrass will need to change as the climate warms,” Professor Campbell said. Ph.D. candidate Nicole Said from ECU’s Center for Marine Ecosystem Research said that not all seagrass species faced the same climate risk, with her research findings on Western Australian seagrass ecosystems indicating that subtidal seagrass meadows could be restored with more heat-resistant populations of the same species. “By identifying and sourcing heat-tolerant populations—sometimes just kilometers away—we can translate this knowledge into on-the-ground action, incorporating resilient populations into restoration to create climate-ready meadows,” Ms. Said explained. West coast Ms. Said is lead author of the study “Seagrasses are most vulnerable to marine heat waves in tropical zones: local‐scale and broad climatic zone variation in thermal tolerances,” which looked at six species along the Western Australian coast, spanning broad thermal gradients from temperate to tropical climates. The study is published in the journal New Phytologist. “Western Australia is an ideal setting for studying seagrass thermal tolerances, and there is a critical need for this data due to WA being a global hotspot for marine climate impacts,” Ms. Said explained. “We can use this information to look at which species might be vulnerable during future marine heat waves, and which ones we should focus our conservation value on.” The study revealed that seagrasses are most vulnerable to marine heat waves in tropical zones. It also showed that climate risk varied across seagrass species, with a 10-degree Celsius difference in thermal optima, and even neighboring populations showed different heat tolerances. “Some populations are better equipped to deal with the heat, and in some cases, the tough ones might be growing next door,” Ms. Said explained. “This shows that not all species face the same level of risk from climate change, and a one-size-fits-all approach is not appropriate for management of thermally vulnerable seagrass species.” The findings could also benefit restoration of seagrass meadows that have already suffered from thermal warming and marine heat wave events. “We can use this information to help build climate-ready meadows, by migrating plants or seeds from more heat-resistant populations into thermally vulnerable areas.” East coast Professor Campbell’s study “Varying vulnerabilities: Seagrass species under threat from prolonged ocean warming” is a paper published in Limnology and Oceanography that examined the impacts of elevated water temperatures on five intertidal species in Gladstone, Queensland, with a focus on improving seagrass restoration. “This study offers an understanding of how climate change might impact these seagrasses, whose ecological functions are not easily replaced once lost,” Professor Campbell said. “Seagrasses are a critically important ecosystem that provides food, shelter and nursery areas for a wide variety of marine life, so with changing climate, it is at risk in different ways. We wanted to understand how these species react when temperatures reach dangerous extremes, which is becoming more common with climate change.” Professor Campbell said they found intertidal pools where the water was more than 40 degrees for weeks on end. “The tide would go out, and the seagrass would be left high and dry, quite often in little, tiny pockets of water which would reach massive temperatures,” Professor Campbell said. “To restore or manage the species, you have to look at the distinct thermal thresholds of the different species—you can’t treat them all as one. “This knowledge helps us to decide which species to plant where—including the best substrate and water depth; so we can restore these ecosystems more effectively.” Professor Campbell said the species she studied were commonly found in Australia and other parts of the world, with the outcomes leading to global impact. “There were two species that were really good candidates for future-proofing restoration in regions that are warming up,” Professor Campbell said. “Two were highly vulnerable and will require more protection from heat stress, or if you’re going to restore them, you need to find micro-climates that are cooler for them—for example, if they are in the sub-tropics, you would look at temperate areas to restore them.” More information: This article is republished from PHYS.ORG and provided by the Edith Cowan University. Nicole Said et al, Seagrasses are most vulnerable to marine heatwaves in tropical zones: local‐scale and broad climatic zone variation in thermal tolerances, New Phytologist (2025). DOI: 10.1111/nph.70742 Marnie L. Campbell et al, Varying vulnerabilities: Seagrass species under threat from prolonged ocean warming, Limnology and Oceanography (2025). DOI: 10.1002/lno.70156