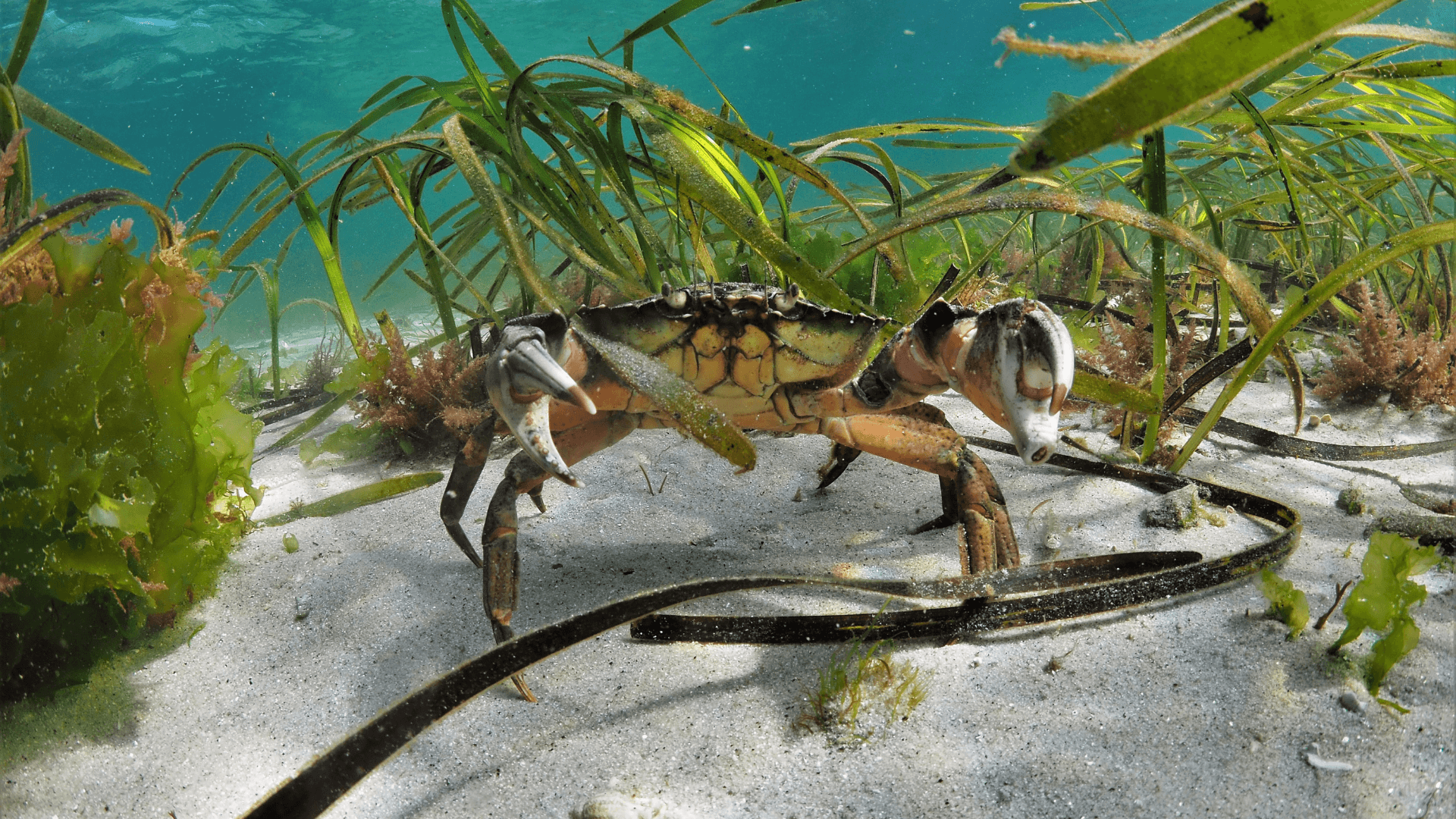

Shore crab – Creatures that call seagrass home

In this blog series, our Conservation Trainee Abi David explores some of the amazing creatures that call seagrass meadows their home. The shore crab, also known as the green crab, are contentious within the seagrass world. They have important ecological roles within their habitats, but their tendency towards destruction and invading habitats has led to them becoming a problematic species. The green crab is a species of variety. They live in shallow marine and estuarine habitats, generally preferring sheltered environments with muddy or sandy sediments. Adults can tolerate a broad spectrum of salinities – between 4 to 52 parts per thousand – and temperatures – from 0 to 30°C. However, this differs between populations, with some being more tolerant than others to change. There is also a wide range of colour variations within the species. Individuals can be green, brown, grey or red and this is largely dependent on local environmental conditions but does also have a slight genetic component. For instance, red-coloured individuals have been linked with delayed moulting and a tendency to have thicker carapace and increased aggression. However, they are less tolerant of environmental stress as a result of a higher metabolic demand compared to green individuals. Crabs have a hard exoskeleton called a carapace. Once or twice a year they will moult their carapace, usually at night. Each moult will increase the body size by 20-33%. The process starts with the crab absorbing calcium carbonate from the old skeleton. Enzymes then break down tissue connections to the old shell as muscles and tissues start secreting a new, softer shell. Absorbing seawater helps the crab puff up like a balloon, cracking the old shell and allowing the crab to climb out. It takes a few weeks for the new shell to harden. In the meantime, the crab continues to fill its tissues with seawater whilst the new shell is soft, ensuring there is plenty of room for growth. Juveniles can moult up to 10 times within their first year if conditions are good, but after reaching maturity will generally only moult once a year. Seagrass with a Green Shore crab (Carcinus maenas), Isles of Scilly, Cornwall, UK Credit Michiel Vos Ocean Image Bank Like a lot of species, green crabs can be affected by parasites. One of the most common parasites they become infected with is the crab hacker barnacle Sacculina carcini. When crabs are at their most delicate after moult, the barnacle can infect its host by injecting a chitin needle into the host and crawling inside the main body cavity of the crab. Once attached, it spreads tendrils inside the host crab, taking over the stomach, intestines, and nervous system to allow the parasite to absorb nutrients and control the hosts behaviour. The parasite will lay eggs on the crabs body and due to the parasites control over crab behaviours, the crab will protect these eggs like they are its own. At this point you may be thinking – that’s pretty grim, but what is cool is the infection effectively castrates male crab hosts and causes them to develop female characteristics and if for whatever reason the parasite is removed from the host, female crabs tend to regenerate their ovaries, but for males, permanent sex change occurs and ovarian tissue develops. As a result of their tolerance to a wide range of conditions, shore crabs are incredibly invasive – even being listed as one of the top 100 invasive species, a list dedicated to the worlds most harmful invasive species that can seriously impact ecosystems. The species is native to the North-East Atlantic and Baltic sea but has colonised areas of Australia, South Africa, South America and both coasts of North America. Global shipping routes are the main cause of this spread. As microscopic larvae, the crabs get caught up in ship ballasts and are transported around the globe. They can also spread due to sea planes, packing materials like seaweeds used to ship live marine organisms and inside bivalves that are moved for aquaculture. What is the link between green crabs and seagrass? Up until now you may have been thinking ‘green crabs are just going about their business, what’s wrong with that?’ but people trying to restore seagrass may disagree with you. There are anecdotal stories from restoration teams and scientists who have been out planting seagrass shoots only to spot a crab scuttling along behind them and pulling out the freshly planted seagrass shoots. Studies have found crabs can damage seagrass when they dig about in the sediment for clams and other invertebrates as this process of bioturbation exposes and uproots shoots. At our nursery in Laugharne, we have spotted seagrass leaves that appear to have been snipped or ripped out by crabs, and seeds mysteriously disappearing after being planted. However, these problems tend to be most prevalent where they are invasive and there are low numbers of predators. In habitats where they are native and numbers are under control – destructive behaviours have a reduced impact and are just a natural part of the ecosystem. Like any creature, crabs have an important niche within their natural habitats. As a generalist feeder, they scavenge and eat dead creatures and detritus on the sea floor that otherwise would rot and cause nutrient build up, which can potentially lead to disease. By eating a wide variety of prey, they help keep populations under control. However, where green crab are invasive or numbers are too high, this can become detrimental. Seagrass meadows are home to a lot of the species crabs will eat, so act as an all-day buffet. Additionally, young crabs are more vulnerable to predation and seek refuge amongst seagrass, with leaves providing cover from birds and fish swimming around above. In areas where they are invasive and populations are too high, it is becoming a popular solution for people to eat them. In New England for example, invasive crab populations are high. In 2019 ‘The Green Crab Cookbook’ was released where each recipe