The Forgotten Meadows of Northern Ireland

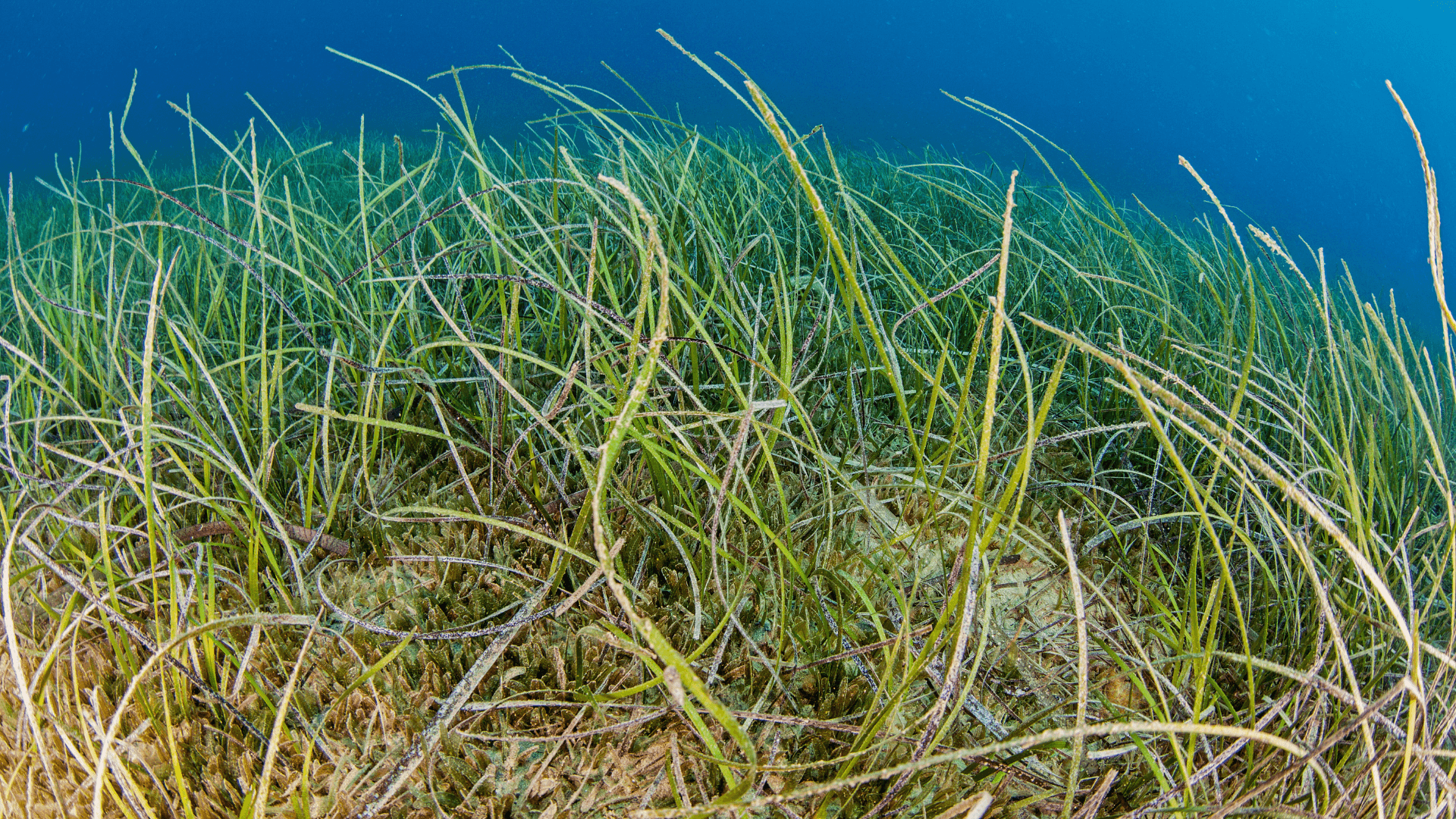

Grace Cutler, one of our 2025-26 Project Seagrass interns, reflects on Rebekah Bajkó’s research, Coastal Roots: The History of Seagrass in Northern Ireland. Northern Irish Seagrass In November 2025, I attended the UK Seagrass Symposium, an exciting conference hosted every two years to highlight the current state of seagrass research within the UK. It was an incredible event that inspired hope and determination, alongside furthering my own caffeine addiction. However, there was one talk in particular, delivered on the first day, that stuck with me for the remainder of the conference, delivered by the researcher Rebekah Bajkó. It was during the ‘Anthropogenic pressure and Environmental drivers of seagrass decline’ segment where Bajkó explored the history of seagrass in Northern Ireland. Here, they highlighted a critical issue that had been wriggling at the back of my mind since my journey into seagrass research began. Where is all the Northern Irish Seagrass? A History of Seagrass It turns out, seagrass has been on our doorstep for a long time. The first record of the common eelgrass (Zostera marina) date back to the 18th century where it grew in such abundance, beaches were described as having a ‘greenish tinge’, carpeting the likes of Belfast Lough with grassy gold. And it’s not just seagrass researchers that view it this way. A letter from a man known as A. MacDougall wrote to the Chief Secretary, William lamb, in 1829, inquiring after a patent for the manufacturing of Seagrass (who intended to use it as mattress stuffing). It wasn’t just humans that sort after these meadows. Brent geese (Branta bernicla), which are known for travelling to Strangford Lough, would feed on the eelgrass across the country. The coastlines also used to contain small populations of Hippocampus hippocampus, the short-snouted seahorse, which still remains as a symbol of Belfast on the city’s crest (Belfast City Hall, n.c). Their appearance in our waters coincide with the period of time when seagrass meadows were at their healthiest. There comes a sense of pride with having such interesting species and habitats next to our homes. Much to my own surprise, my home village (Dundrum, Co. Down) was the first-time dwarf eelgrass (Zostera Noltii) was discovered in Northern Ireland, in 1914. Dundrum, Northern Ireland, Photo taken by Grace Cutler Yet, despite their abundance and importance for life in Northern Ireland, in the late 19th century, seagrasses began to decline. Much like the rest of the UK, it is believed with increasing anthropogenic stressors, such as land-use change and nutrient input, seagrass became less resilient. This left it open to the seagrass wasting disease. The lack of seagrass in Northern Ireland has since been felt by those living on coastlines since its initial decline. Particularly, in Belfast, without the wave attenuation seagrass provided, waves break on beaches causing rapid degradations of its shorelines. Furthermore, the loss of seagrass has been felt by birders, who noticed a decline in avian species, and called for an investigation during the early stage of seagrass decline. What is Left? Since the 1940s, there has been a small recovery seen in seagrass species. Although seagrass has completely disappeared from Belfast Lough it remains in Strangford Lough and is dotted throughout the country. Records of seagrass (1794-1994) layered with the extent of seagrass in 2023 across the Northern Irish coast. Map lines show study areas and not necessarily national boundaries (Bajkó, R., Millar, R., & Smyth, D., 2025) So why is there so little seagrass along Northern Irish coastlines? Currently, there are no active restoration programmes aiming to restore seagrass in Northern Ireland. Belfast Lough has not seen seagrass for over 60 years and is unlikely to in its current state. Strangford Lough on the other hand has great potential for recovery and has already experienced natural recovery of Zostera marina and has the largest extent of Zostera noltii across the whole island. Seagrass researchers like Rebekah Bajkó and Heidi McIlvenny (a PhD student who focuses on assessing the sediment organic stocks in Northern Irish seagrass meadows) are beginning this conversation. If you are interested in any of the information mentioned here, I highly recommend reading Bajkó’s, original paper which goes into much greater detail on this subject. Yet, more attention needs to be brought to Northern Ireland so we can see substantial increases in seagrass meadows. Until then, they may forever remain our forgotten meadows. References Bajkó, R., Millar, R., & Smyth, D. (2025). “Coastal roots: the history of seagrass in Northern Ireland.” Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 105, Article e63. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315425100106. Belfast City Hall (no date). “History of Belfast city hall.” Available at: https://www.belfastcity.gov.uk/things-to-do/city-hall/history-of-belfast-city-hall. (Accessed: 8 January 2026)

How the Seagrass Essential Ocean Variable can support more effective monitoring and management

Current estimates of the global extent of seagrass range from between 160,000-266,000km. Such a high degree of uncertainty presents challenges for researchers and managers and their ability to make informed decisions which account for the changing status of seagrass ecosystems. Key to improving our understanding of seagrass presence and absence, identified as one of the six Global Challenges facing effective seagrass conservation, is the collection and integration of interoperable data on seagrass extent. A new paper published in Bioscience from members of the Coordinated Global Research Assessment of Seagrass Systems working group outlines how the Seagrass Essential Ocean Variable can help us to address this challenge. This paper was co-written by members of our Project Seagrass team. Achieving our goals for seagrass conservation requires reliable information on the status and trends of seagrasses and the organisms that associate with them, yet seagrass variables measured and the methods for doing so vary widely across projects and organisations, presenting challenges for comparisons across studies. This new paper provides a global framework for seagrass monitoring as an Essential Ocean Variable of the Global Ocean Observing System, key to aligning seagrass researchers and managers around a common approach to seagrass monitoring. Implementing these guidelines will support the collection of more comparable, compatible, and combinable seagrass data. The Seagrass Essential Ocean Variable contains three priority measurements to maximise compatibility across data sets: Seagrass percentage cover Seagrass species composition (the identify and relative abundances of seagrass species in an area) Seagrass areal extent (the horizontal extent of seagrass at the meadow of seascape scale These three priority measurements collectively have been identified to provide the most useful assessment of seagrass status and change at landscape scales, addressing most scientific, management, and policy needs and targets. The Essential Ocean Variable also includes further supporting variables relating to biological and environment factors. Seagrass monitoring using SeagrassSpotter At Project Seagrass we’re well placed to contribute to this global process with our OpenAccess SeagrassSpotter.org platform collecting georeferenced data on seagrass percentage cover and species composition. In 2026 we will also be launching a complementary app called SeagrassTracker which will help scientists report, share, and archive data on seagrass spatial extent. These platforms are all linked to the Global Ocean Observing System. Key to the Seagrass Essential Ocean Variable is a commitment to collaborate. If utilised across widely, the EOV will support the creation of a growing resource of seagrass data that is maximally compatible and supports more reliable local research and better-informed management.